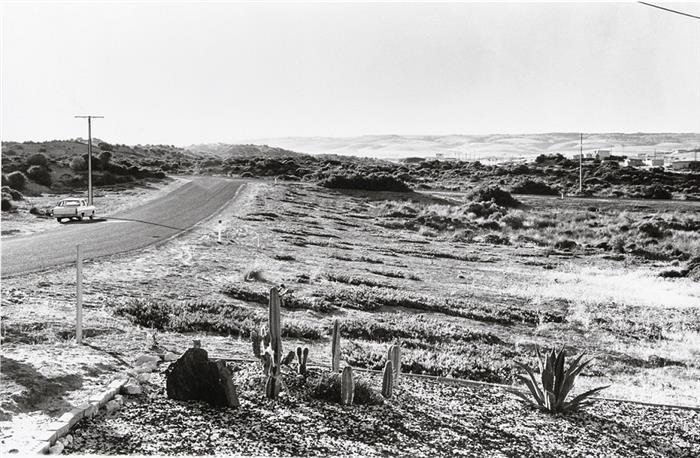

Felicia 16 (Goolwa, Fleurieu Peninsula), 1976

Just Allowing it to Be: A Conversation with Ian North1

This is an edited excerpt of a conversation between artist Ian North and curator Pedro de Almeida that was undertaken in North’s studio in Adelaide, Australia in December 2012. The impetus for the meeting was research for a presentation of North’s solo exhibition of his body of work Felicia: South Australia 1973-1978 at the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, accompanied by an artist’s monograph by the same name.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: To begin at the beginning, Ian. You were born in 1945 in Wellington, immigrating to Adelaide in 1971. What prompted the move to Australia?

IAN NORTH: I was working as a regional gallery director, a job I held from 1969 in Palmerston North, New Zealand.2 I enjoyed the work hugely but felt a little constricted in New Zealand. The art scene was very vital and some very good artists were active there at the time but I wanted to work in a slightly bigger situation. This was known to the council of the gallery I worked for and one day one of its members said, ‘by the way Ian, do you know there’s a job going in Adelaide?’ I said, ‘where’s Adelaide?’ (laughs).

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: The Felicia portfolio, dated from 1973 to 1978, encompasses the period of a young man from the age of 28 to 33 who was Curator of Paintings at the Art Gallery of South Australia. During this period you curated and wrote the catalogue essay for the Hans Heysen Centenary Retrospective. How did you find the balance between your private desire to photograph and your professional role and responsibilities?

IAN NORTH: My main thrust as a curator at that time was to switch the collection away from an English, rather backward-looking focus to a much more contemporary-looking focus to which end I rejigged the acquisition of international art and initiated the Link Exhibition series of contemporary Australian art. I also wrote a book on Dorrit Black and coordinated the Margaret Preston retrospective of 1980, among other things. What it had to

do with my practice as a photographer? I think doing exercises like the Preston, Black and Heysen projects were quite distinct from my photographic interests and really had no bearing on them. To be honest Hans Heysen was something of a duty to us salty young curators, we had to do it as being the appropriate gallery to pay him attention … Photography was a compulsion however. I had this crazy desire to make artworks which was very inconvenient. I had felt it very strongly earlier as a reluctant university student at the age of eighteen in Wellington, stopped in my tracks riding my motorbike or just walking, by the concatenation of lamp posts, architecture and trees, all swaying and tilting between a grey sky and a grey road typically, and feeling compelled to capture it all in some way. Photography seemed to be an appropriately quick way to do that.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: Quick but not quick by today’s standards. After pressing the shutter button did you have an impatient sense of anticipation to see the prints, or were the prints secondary because the experience was mostly in the walking and the observing?

IAN NORTH: The prints were reasonably important to me, although they always disappointed me in those days because they were typically processed by a commercial Kodak lab and they were never any good. So that in itself was a bit of an inhibition for me, I suppose, in terms of realising the full potential of photography and its capacity to be an art medium in its own right. I was somewhat aware that it could be. I was aware of the work of Ansel Adams fairly early on through publications, LIFE magazine published his work from time to time… and I remember the photographer Brian Brake came out with a book on New Zealand, the landscape principally, which was surprisingly powerful.3 It got away from the calendar style of imagery which was so boring. In fact I suddenly remember going to a tobacconist or deli as a young child, aged about eleven or twelve, with my parents and making a derogatory comment about the postcards on the rack in a loud voice and being accosted by the proprietor and embarrassing my parents. I had completely forgotten that! But jumping back to days at the Art Gallery of South Australia, by then I had learned to forcibly discipline myself to be able to do academic and curatorial work while still making artwork at other times.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: To expand on that professional discipline, your experiences during a period when the Australian art industry was undergoing massive change were coloured by the professional boundaries that were, by today’s standards, relatively impermeable. Was it overt back then, that a curator couldn’t be a practicing artist? Were the discouragements simply due to concerns over potential conflicts of interest in financial matters relating to acquisitions, or were there deeper conceptual reasons, where some people just didn’t believe one could wear the two hats?

Felicia 15 (Goolwa, Fleurieu Peninsula), 1976

IAN NORTH: Both. Definitely both. It was strongly overt in my consciousness … I was very fortunate indeed when I first came to Adelaide to be given the job of co-curating an exhibition of the Australian landscape for the 1972 Festival. In those days we used to put together exhibitions far more quickly than they do today. The other two people working with me on that show were Daniel Thomas from the Art Gallery of New South Wales and Frances McCarthy as she then was then, later Frances Lindsay.4 Daniel was of course the senior partner of the trio, a dominating if very generous influence. He was strongly against curators being artists themselves even though he worked with the famous Tony Tuckson and admired Tony’s work.5 I can hear his voice and Francis’ now: ‘curators don’t paint!’ … Talking of extra-curricular activities I was also involved with the setting up of the Experimental Art Foundation as one of the first Council members in 1974, and though it was principally Donald Brook’s baby I was an enthusiastic supporter.6 At the same time I was instrumental in buying works for the Art Gallery of South Australia by a range of photographers and other artists who were working in a way that I thought was important, artists with various degrees of conceptual orientation—without separating out the photographers, people like Jan Dibbets, Hamish Fulton, Richard Long, Gerhard Richter, Kenneth Noland, Charles Simonds and Dennis Oppenheim. I went overseas in 1972 and approached two people to see if they would act as spotters for us—the curator at the Tate Gallery, Ronald Alley, and John Stringer at the Museum of Modern Art in New York,7 and when I came back John Baily, the director at the Art Gallery of South Australia, agreed that they should be spotters and I worked with them to enhance the collection. But I had this secret life beyond even all that.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: Were there others? Was it like ‘reds under the bed?’ Were there other curators—colleagues of yours—that had this secret life?

IAN NORTH: Not to my knowledge. It was very secret. I was responding to things around the streets and environs of Adelaide, the kind of things we now see in the Felicia portfolio that seem to be largely—but I think not completely— antithetical to conceptual work. I never really one hundred per cent bought the full conceptual bit even though I was professionally interested in it, and I think it played into later work, into the Canberra Suite, for example. But even in the midst of my deconstructive work in the mid 1980s I still honoured the aesthetic, for want of a better term, both in terms of overt content -celebrating and critiquing the romantic tradition—and the mode of making. I thought I had to be intellectually interested in conceptualism and indeed was professionally interested in it but nonetheless it didn’t satisfy me.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: You didn’t photograph every building on Rundle Street for instance.8

IAN NORTH: No, nothing like a particular project in that fashion. It was much more intuitive, much more compulsive and unpredictable … Just as I kept it secret at the art gallery I kept it secret from my colleagues at the Experimental Art Foundation. In fact, I hate to say it, but I think I was the first member of its initial Council to leave mainly because I just couldn’t hack the extreme non-aesthetic emphasis of Donald Brook’s theories. I still can’t. I’ve been debating the matter with him for thirty or forty years. He’s still a good friend (laughs).

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: At what point in your mind did the Felicia series formulate into what it is now a portfolio of thirty-eight photographs?

IAN NORTH: I wasn’t aware of creating a series as such at the time—yet I was certainly aware of pursuing persistent ideas, ones that I couldn’t really understand completely except that they didn’t conform to a conceptual program and they didn’t conform to the conventional landscape and urban photography genres either, as far as I knew them … I believe I was conscious of recurrent motifs and interests: the edge of civilisation, the dichotomy and interface of nature and culture, another very strong aspect. I was also aware of repetition: the piles of bricks and earth, for example, the desire to create something permanent in the shifting sands of the South Australian desert … I set up a darkroom at home, as you might expect in the laundry, and if I got home early enough—in those days we were kicked out of the gallery at six o’clock by security staff, it was pre-computers so we tended not to work at home all that much—it was possible if you got a reasonably early start in the evening to do a bit of work. So I became quite compulsive about printing up some of the images. I didn’t have time to address all the works as you see them now but I certainly worked on a fair few of them, in some cases printing and printing and printing and re-printing and re-printing and re-printing, such are those elusive middle greys, teaching myself techniques as I went. I don’t know what influences were working on me at all because you have to remember the early ’70s were prior to the extraordinary explosion of publications that happened later in the decade. There was a handful of histories and the odd monograph or two, but really there was very little information to go on and very little awareness of what other people were doing, although that quite quickly changed, of course … By 1979 I started seeing things, the world, in colour and moved to colour photography having laboured through the previous decade to try and perfect black-and-white techniques. But to answer your question directly it was in part the interest of the Art Gallery of South Australia in works of mine from the 1970s that prompted my formulation of Felicia. There was a survey show of my work that Maria Zagala curated for the Gallery two years ago and seeing some of that work on the wall made me realise there was more depth and shape to it than I had fully realised.9

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: I think the feelings of isolation worked in your favour.

IAN NORTH: Yes, I think so now, that’s right. I’m very interested to hear you say that and heartened by it actually.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: If we go through the work: you have suburban scenes of houses, streets and laneways in Adelaide and surrounds, as well as some photographs of the peninsulas, north and south. Immediately I’m struck by the continuation of motifs, particularly of power lines and clouds; defining spatial arrangements as abstract lines in the sky, intersecting clouds as a metaphorical link between nature’s own source of electricity and the spread of this civilisation across some very arid country, with these almost despondent suburban homes and other shelters underscoring the expanse of land and sky across South Australia. There’s almost a sense of manifest destiny, which alludes to the title of a later series of works by you. Were you self-consciously aware at the time of employing the telegraph pole with this symbolic potential, as a kind of sentinel motif that corresponds to the few human figures in your landscapes, or is that just what caught your eye?

IAN NORTH: I certainly was somehow intuitively accepting of them, I didn’t try and cut them out—yet I have never identified with reductive formalism and the eye is of course connected to the brain, to one’s culture and its countless stories, to state the bleeding obvious. I was interested in power poles and lines way back in Wellington days, and while I can’t remember this at all, I imagine that I became aware fairly early on in Adelaide of the overland telegraph established between Darwin and South Australia in the late nineteenth century, connecting Australia to the world. … At a certain stage of life one starts looking back, as well as forwards. I’m at that stage. For example I feel that the spareness and sparseness which are aspects of Felicia feed into the Canberra Suite along with a tamped down lyricism, and vice versa …a looping forward and back, something I am beginning to see in all my work.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: The thing that really hits me is the temperament of your observation as something unelaborated in the best sense of that word. I find it interesting if somewhat frustrating that in the blurb that the Art Gallery of New South Wales wrote to describe your Canberra Suite for their recent exhibition, Photography & Place: Australian Landscape Photography 1970s until Now they said, ‘these ironic images infer instead a sense of absurdity in the urban Australian context,’ which I completely disagree with. You don’t have that snarky, ironic stance and certainly there’s no absurdity.10

Felicia 18 (Goolwa, Fleurieu Peninsula), 1976

IAN NORTH: No, not at all. There’s a kind of surrealism perhaps.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: In addition there’s nil sentimentality. As I’ve come to get to know you they’re quite like your personality in a way, like an iceberg, nine tenths below the surface (laughs).

IAN NORTH: Interesting.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: Looking through my notes, you have here a statement, Self-portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, written by you in the third person.11 What I find interesting is this line, ‘the expanse of South Australia and its overarching light captivated him.’ When I was thinking of that light¬—we spoke a little of this when we viewed the prints earlier—I think of David Goldblatt, his early work in South Africa.12 I know that he’s spoken about similar concerns. I think most young photographers of a certain generation—and this may still be the case for some young people today in the digital era—begin by looking at the European and North American classics of the medium, for instance when they get their hands on a Cartier-Bresson book they fall in love with Paris like everyone else and fall in love with the look of those photographs and, putting Cartier-Bresson’s subjects and content aside, when you go out and hit the streets of the Australian suburbs and you come back and develop your film, especially black-and-white film—though the same holds true for digital images—you realise the photographs look nothing like Cartier-Bresson’s because the quality of the light is so different; you don’t get the light reflecting off cobblestones, you don’t get that magical European diffused light that makes the world look like it’s been lit by a soft box. I know that Goldblatt, when he started photographing in South Africa in the 1950s, really struggled with the quality of light and to accept a tin-looking sky because if you have big, blue cloudless skies you don’t get that subtle drama in tones and it took him a long time to make a virtue of that. You don’t seem to have had that struggle. From the get-go, at least in the Felicia series, as you said, you ‘allowed it to be’ and were accepting of Australian light and its expansiveness. Clearly in some of the images you’re shooting at midday with brilliant skies and very harsh shadows, not looking for drama, not looking for the gloaming, and I find that very prescient of contemporary sensibilities.

IAN NORTH: It was the very quality I was trying to capture. I was very aware of the expansiveness of the landscape, the flatness of it and the contrast with the green, vertiginous and dark landscape of New Zealand. But I really revelled in it in a way, even though it felt a little alien as well. Talking of Cartier-Bresson, people don’t appear much in my work, as you will have noticed…I wasn’t much enraptured by post-war humanism, or photojournalism for that matter, notwithstanding seeing The Family of Man as a teenager in Wellington, as I very vaguely recall. Felicia I feel you could almost see as a qualifying corrective to Dunstan and Whitlam’s utopianism, laudable though that might have been.13 Yes, for me it’s all about acceptance in the end, a kind of ecstatic acceptance; a gob-smacking ‘photograph me’ kind of acceptance where everything comes together. And it’s not about the quaintness of the architecture or the oddity of human habitation or a desire to record things for history or any reason like that, it’s just the sheer uncanniness of all these elements coming together into some sort of significant concatenation. Almost a metaphysical quality, actually.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: I really understand your approach as being about the quality of observation. You don’t have a conceptualist’s irony—it’s not about that—and while of course these images are historical by default they don’t have a specific historical agency. It’s that well-worn phrase of Walker Evans’: it’s a ‘documentary style’ because documents have purpose and all art should be useless.14 And then there’s your sequencing: it might be chronological but clearly there’s a lot of thought in terms of the way the series begins with no view at all, with a panorama of a corrugated iron fence, progressing to views of the edge of civilisation as you put it, going out into the peninsulas, before coming back into the minutiae of suburbia with counterpoints to the first image with, again, claustrophobic views of curtained, shielded windows or some shrubbery in a backyard with no foreground or middle ground, only a backdrop of fences as psychological as much as geographical barriers, and ending the series on this image of a dirt track leading to an horizon of ocean, on the precipice of the Great Australian Bight.

IAN NORTH: And a little bit of grunge early on with the power point.

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: The power point ties into the power lines that signal these points in space in otherwise desolate landscapes and back again into civilisation. And I’m struck by the darkness of the interiors. I just watched, not for the first time, Wake in Fright, which you’d remember.15 It was on TV only a couple of weeks ago and, of course, I was enjoying a few beers watching it…

IAN NORTH: Wonderful!

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: … and there’s that scene with Donald Pleasence’s character just before the infamous kangaroo hunting scene which is extraordinary. He’s living in this ramshackle hovel and before they go out ’roo shooting at night there’s that sharp, violent Australian sun outdoors and yet he’s living in this completely dark, dank tin shed.

IAN NORTH: Yeah, that’s right (laughs).

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: There’s something about white Australian settlement and its paradoxical simultaneous fear and wonder of that light.

IAN NORTH: Speaking of light, I have a memory of a statement by Robert Adams which resonated strongly with me at the time I first encountered it, whenever that was, very much to the effect of what we were saying about my work, that he was not about historical documentation or about criticism. I don’t remember his exact words, but recall that he spoke about the unifying effect of light over natural grandeur and human desecration of the landscape.16

PEDRO DE ALMEIDA: I’d like to conclude by touching on the period immediately following the Felicia series. In 1980 you moved to Canberra as the Foundation Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia. To be more specific, if you can touch on your initial experiences of taking up that position, being such an important one, and secondly how that changed your practice, particularly in terms of your previous comment about how you began to see in colour and the development of the Canberra Suite? And lastly, can you speak a little about what you’re working on now, for instance you mentioned in our previous conversations your recent trip to Antarctica?

IAN NORTH: I don’t think it changed my practice at all because it was a bit like when I was at the Art Gallery of South Australia; you asked about the nature of my photography vis-à-vis Hans Heysen or Dorrit Black or even the Experimental Art Foundation, it’s as if those considerations belonged in the public sphere and my own photography was in a private world of its own. Having said that I can now confess that I was a bit reluctant to get into cataloguing material at the National Gallery of Australia17 because I didn’t want to be influenced by other people, but by then I was sufficiently practiced in the schizophrenic art of keeping the public role and the private role in separate boxes. The Canberra Suite was inevitable really because it was like photographing around Adelaide with knobs on; Canberra was more surreal, the air there is sub-alpine and more crystalline—the meeting of nature and culture was just everywhere, penetrating the innermost recesses of suburbia, so it seemed to me. You got wonderful skies no matter how uninspired the architecture might be. My concern was not to dwell on that banality but to capture gestalts, these concatenations of built form and nature, especially the wonderful skies, which formed coherent wholes … As to what I’m working on now, you’re quite right, I did take a trip to Antarctica earlier this year.18 I was expecting to be impressed by towering bergs, à la Hurley, and there were certainly a number of those, but my main impression was one of gravity and entropy, of melting, of things flattening out, so I’ll be working with that, perhaps using paint as well as photography.

[nggallery id=469]

Biographies

Ian North (b. 1945, Wellington, New Zealand) is an artist, writer and professor who is recognised—as an artist and, after an illustrious almost five-decade career as a curator, academic, educator and professional committee and board member—as a leading figure in the development of Australian art and photography since the 1970s. Originally from New Zealand, North immigrated to Australia in 1971. North’s photographic practice began in the early 1960s when he photographed the streets of Wellington, New Zealand from his motorbike. The interest in his immediate surroundings developed from a youthful appreciation of the work of J.M.W. Turner and the aesthetics of landscape. During these formative years North found the makings of a visual dialogue between photography, painting and landscape. North’s career in museums spanned fifteen years during which time he consistently created work as an artist but did not exhibit due to professional reasons. His roles during this time included Director, Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North, New Zealand (1969-71); Curator of Paintings, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide (1971-80); and Foundation Curator of Photography and Head of Photography Department, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (1980-84). He has exhibited his work regularly since 1985 and his work is held in Australian national, state and private collections.

Pedro de Almeida is a curator, programmer, arts manager and writer. He is Program Manager at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, and a regular contributor to Art & Australia, Art Monthly Australia, exhibition catalogues and other publications.

Notes

[1] This is an edited excerpt of a transcript of a conversation between Ian North and Pedro de Almeida over 15 and 16 December 2012. De Almeida’s travel to Adelaide was assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body, through a Visual Arts Board Skills & Arts Development Grant.

[2] Ian North was Director of Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North, New Zealand from 1969 to 1971 where he organised over twenty exhibitions a year with emphasis on contemporary art, including several for national tour, one of which, Maori in Focus, broke new ground as an exhibition of nineteenth-century photographs of Maori in an art context.

[3] New Zealand: Gift of the Sea, Brian Brake (photographs) and Maurice Shadbolt (text), Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch, 1963, 149 pp., was an expanded re-worked version of the photo-essay by the same title originally commissioned from Brake in 1960 and published by National Geographic in 1962. Brian Brake (b. 1927, Wellington, New Zealand, d. 1988) was one of New Zealand’s most internationally successful photographers, becoming a full member of the Magnum photo agency from 1957 to 1967 and engaging in decades of prolific photographic, publishing and filmmaking projects across Asia and elsewhere.

[4] The Australian Landscape was presented at the Art Gallery of South Australia as part of the 1972 Adelaide Festival of the Arts, later touring nationally. At the time, Daniel Thomas was Senior Curator, Australian Art, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (1958-78); Frances McCarthy, later known as Frances Lindsay, was Assistant Curator, Australian Art, at the National Gallery of Victoria before being appointed Assistant Curator, Australian Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales later that year.

[5] Tony (John Anthony) Tuckson (b. 1921, Port Said, Egypt, d. 1973) was an abstract painter who was appointed as Assistant to the Director, Hal Missingham, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (1950-57) and later Deputy Director (1957-73) during which time he was recognised for his pioneering role in the aesthetic (as opposed to solely anthropological) appreciation and acquisition of Indigenous art from Australia, the Torres Strait and Melanesia. Tuckson’s first solo exhibition was held in 1970 at Watters Gallery, Sydney, presenting sixty-four paintings mostly from the period 1958-64. He held a second solo show six months before his death in November 1973.

[6] The Experimental Art Foundation (now the Australian Experimental Art Foundation) was established in 1974 by a small group of Adelaide artists and theorists including its inaugural Director Noel Sheridan (b. 1936, Dublin, Ireland, d. 2006); Donald Brook (b. 1927, Leeds, England), Clifford Frith (b. 1924, London, England), Bert Flugelman (b. 1923, Vienna, Austria), Richard Llewellyn (b. 1936, Strathalbyn, South Australia, d. 2004) and Ian North, who was a Foundation Council Member from 1974 to 1976. The Experimental Art Foundation’s mission was and remains to promote an idea of art as ‘radical and only incidentally aesthetic’ (source: http://www.eaf.asn.au/mission_statement.html).

[7] In 1972 North undertook an eight-week study tour of museums and private galleries in Italy, Germany, France, England and the United States. Ronald Alley (b. 1926, Bristol, England, d. 1999) was the first Keeper of the Modern Collection at the Tate Gallery from 1965 to his retirement in 1986, having first joined the Tate in 1951, and is recognised for his contribution to cataloguing practices of the Tate’s modern collections. John Stringer (b .1937, Melbourne, d. 2007) was appointed Assistant Curator of Prints at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1957, subsequently moving into exhibition management. He was co-curator with Brian Finemore of The Field exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1968, moving to New York in 1970 to become Assistant Manager, International Program, at the Museum of Modern Art. He subsequently ran the Centre for Inter-American Relations in New York for ten years, before becoming curator of the Stokes collection, Perth, from 1992.

[8] Cf. The American artist Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on Sunset Strip, 1966, or his Twenty-six Gasoline Stations, 1963.

[9] Ian North Photographs 1974-2009 was presented at the Art Gallery of South Australia, 5 June – 26 September 2010, curated by Maria Zagala, Associate Curator, Prints, Drawings & Photographs.

[10] Art Gallery of New South Wales Education Kit, p. 8., to accompany Photography & Place: Australian Landscape Photography 1970s until Now. (source: http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/education/education-materials/education-kits/exhibition-kits/photography-place/).

[11] Ian North, artist’s statement, ‘Self-portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’, 2011. Cf. the presentation of the Felicia Portfolio in the group exhibition Heartland, curated by Nici Cumpston and Lisa Slade, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2013.

[12] David Goldblatt (b. 1930, Randfontein, Gauteng Province, South Africa) is one of South Africa’s most successful photographers, having documented South African society and landscapes since the 1950s during the period of apartheid and beyond. In 1998 he was the first South African to be given a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. In 1975 the National Gallery of Victoria presented David Goldblatt, his second solo exhibition (North has no memory of having seen this exhibition).

[13] The Family of Man was a major exhibition of photography curated by Edward Steichen and first presented at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1955 before travelling to dozens of countries. It instantly became hugely popular with a mass audience for its illustration of the varieties of humanistic approaches to the medium following the Second World War. Donald Allan ‘Don’ Dunstan AC, QC (b. 1926, Suva, Fiji, d. 1999) was a South Australian politician. He became state Labor leader in 1967, and was Premier of South Australia between June 1967 and April 1968, and again between June 1970 and February 1979. Edward Gough Whitlam, AC, QC (b. 1916, Kew Melbourne), known as Gough Whitlam, served as the 21st Prime Minister of Australia. Whitlam led the Australian Labor Party (ALP) to power at the 1972 election and retained government at the 1974 election, before being dismissed by Governor-General Sir John Kerr at the climax of the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis. Both politicians were noted for their innovative reforms across a wide range of social and political issues, including the arts and indigenous affairs.

[14] The relevant quotation is: ‘Documentary is very sophisticated and misleading word. And not really clear. You have to have a sophisticated ear to receive that word. The item should be documentary style. An example of a literal document would be a police photograph of a murder scene. You see, a document has use, whereas art is really useless. Therefore art is never a document, though it certainly can adopt that style.’ In Leslie Katz, ‘Interview with Walker Evans,’ Art in America No. 59, March-April 1971, p .87.

[15] Wake in Fright, directed by the Canadian filmmaker Ted Kotcheff and starring Gary Bond, Donald Pleasence, Jack Thompson and Chips Rafferty, was released in Australia in October 1971. The movie concerns the alcohol-induced travails of an English school teacher on leave from his job who finds himself marooned in the fictional outback town of Bundanyabba at the mercy of the locals and their aggressive, enforced idea of mateship.

[16] Robert Adams (b. 1937, Orange, New Jersey, USA) is an American photographer whose work explores the changing landscapes of the American West, particular locations in the states of Colorado, California and Washington. He was included in the seminal exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape at the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, in 1975, curated by William Jenkins. His writings on photography have been compiled in Why People Photograph: Selected Essays and Reviews, Aperture, New York, 1994, 186 pp., and Beauty in Photography: Essays in Defense of Traditional Values, Aperture, New York, 2005, 112 pp.

[17] North was Foundation Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia (originally the Australian National Gallery until its name change in 1992) for nearly five years, from 1980 to 1984. He was responsible for, among other things, developing policy; research into collections (8,400 exhibition quality works as at June 1983); seeking and recommending acquisitions of Australian and international photography; creating a viable department of photography; recruiting and supervising staff of three curatorial assistants (Isobel Crombie, Helen Ennis and Martyn Jolly); organising the display and conservation of the collections; writing and editing publications, and giving public lectures and media interviews. The acquisition program for photography during this period was the largest of any publicly-funded art museum in the world, and the period of North’s tenure saw large bodies of historical and contemporary Australian and international material coming into the collection, establishing a solid foundation in the crucial years before and immediately after the Gallery opened to the public in October 1982. North’s curatorial overview of the collection was published in the introductory catalogue Australian National Gallery: An Introduction, edited by James Mollison and Laura Murray, 1982, pp. 121-146. The inaugural exhibitions of photography were Australian Photography: Pictorialism to Photojournalism (13 October 1982 – 16 January 1983) followed by International Photography 1920-1980 (10 November 1982 – 30 January 1983).

[18] North also crossed the Pacific from Long Beach, California, to Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, by container vessel in 2006, seeking maritime imagery as for his ocean voyage to East Antarctica in 2012.

(All rights reserved. Text and Images @ Pedro de Almeida and Ian North)