“To me, everything is language. Language allows you to use a limited set of elements to build ever changing and endless worlds.”

Bruno V. Roels’ work encompasses many layers of language, economy, history and repetition which hints a greater understanding of where photography becomes complicit in its indelible position as a conduit for fragmented meaning. What appears to be a formal quality in the work is simply the surface beauty for which these layers operate. Palm trees are not simply palm trees. In Roels’ work, they trigger a greater response about how an image is de-constructed very much in the same way that we question the fundamental relationship between communication and photography. The repetition he employs is inherent in the way in which this repeated communication is used as a tactical tool to challenge meaning through reiteration. Beauty and the relationship to the symbolic and history are components that do not limit the communication of the image, but rather enhance the way in which his images are acquiesced with a nearly mystical possibility. I was lucky to get his time for this interview before his inaugural show at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York.

BF: We have been speaking a bit back and forth via email over a number of things that I hope to cover in this interview, which I should mention now coincides with your show at Howard Greenberg’s gallery. I will start there as I found the idea quite interesting as I know of Howard and his incredible legacy in the field of dealing from a different facet of my photographic life. I was a bit surprised by it all as Howard isn’t known hugely for his work with contemporary imagery. Then I started to think through why Howard would be attracted to the work. First and foremost, the prints you make remind me of paper from the 1930’s or perhaps AGFA Portriga Rapid. They are creamy, nearly vintage looking, which harkens a nostalgia that I assume tripped Howard’s interest. Then on top of which, your aesthetic in its repetition of imagery has a very modernist aesthetic. That is not to present conjecture that you are in any way “aping” that particular nostalgia, but rather that you must have some historical inclinations in making images that Howard probably picked up on. How did you come to work with Howard and would you like to take this opportunity to broadcast which work you will be showing there?

BR: Well, I’m part of Gallery Fifty One’s roster of artists. Gallery Fifty One is a gallery in Antwerp specialized in photography, and they have an international reach. I joined them 4 years ago and I was lucky enough to have my work shown on all the big international photo fairs. It’s hard to express how much it means to have a gallery that believes in what I do and gives me the space and the time to grow. It’s sometimes hard to grasp that they put my work on the wall knowing very well they can show a heavy hitter like Saul Leiter instead, for ten times the money at that.

Howard was among the first to quickly express interest and the ball started rolling from there. To be extremely honest, just looking at the website of those galleries makes me a bit weak at the knees. You can’t love art photography and not be in awe of the collection of artists they represent. To think I’m one of them is enough to make my brain blow a fuse. And that’s not me being a fan boy, it’s more about knowing my place in the world.

I haven’t asked Howard why he’s showing me, but I do notice a renewed interest in modernist photography, which makes sense because those guys were trailblazers, and they knew/cared more about the possibilities of photography (in the broadest sense) than what is considered photography by the mainstream in the 21st Century.

I’m not claiming that I am a trailblazer, but the possibilities of photography interest me, and it’s only natural that I’m drawn to the modernists, their subject matter, and their techniques. (Not just the photographers by the way, but modernism in general is of interest to me (writers, musicians, painters…)

To circle back to the nostalgic vibe in my work: I use Ilford paper that is relatively easy to get (not as straight forward as it used to be). That paper gives me the results I want, but it’s hyperwhite and I hate that. Except for snow, there is nothing that white in nature. So I try to tone it down with coffee, tea, coke etc. The creamy vintage look combined with the subject matter puts my work in a very narrow place: I have to tread carefully not to end up with work that’s dripping with saccharine nostalgia or turns into utter kitsch.

At Howard Greenberg, I’m showing work that fits in my A Palm Tree Is A Palm Tree Is A Palm Tree series. I consider it an introduction of the core of my work to an American audience. I have no idea what to expect from New York collectors in terms of response.

“I see a clear connection between the rise of photography (end of 19th – beginning of 20th Century) and the ‘great discoveries’ on the back of a sprawling colonial empire. It’s part history, part Indiana Jones, part Poirot…”

BF: Your work functions in grids, repetition and multiples. There is a rhythm to it that suggests a language. There is of course as seen through Warhol- a fascination for this repetition that is highly reflective of the crux of capitalism, but also again, the presets of Modernist machine-age repetition of image currency. Warhol is but one example, Ed Ruscha another. I also could make the reference of Ruscha palm trees here for fun. In any event, what attracts you to employ the tactic of repetition and grids within the work?

BR: There are different ways to look at it. To me, everything is language. Language allows you to use a limited set of elements to build ever changing and endless worlds.

Sometimes, when I’m in the dark room, it feels like jazz: playing a standard but mucking about with a blue note, and making it work nonetheless. Allowing variations to bloom and become more than just ‘mistakes’.

Sometimes it’s pure math: take a single item (a negative) and use permutations (time, contrast) to fill a matrix (the composition) with a data set (the separate prints).

Warhol is a big influence, yes, his repetitions are very compelling. What I took from him is the notion that everything becomes interesting if you present enough of it. And, as you point out, there’s a link with the mechanized production that’s at the core of capitalism. In photography, especially in art photography, there’s this annoying concept of ‘a limited edition’. It’s a bit of a bastard move to artificially limit your output because of the market when you consider the reproduction powers of the photographic process.

I took a different approach: I decided to show all the prints at once, making the composition unique. I can’t even reproduce my own work; all pieces are unique.

But I realized that the main reason I’m attracted to grids has more to do with the fact that a grid, or a matrix, offers a very dry, unbiased, almost scientific way to present data sets. A grid brings order to chaos. (Something the Bechers realized as well.)

And -because you brought him up- what attracted me to Ed Ruscha and artists like John Baldessari is their dry way to interact with the world. Ruscha’s early photographic books “Twentysix Gasoline Stations”¸ “A Few Palm Trees”, “Some Los Angeles Apartments”… are so deliciously poker-faced. It’s a quality I appreciate in On Kawara’s work as well. Brilliant ideas, deadpan execution.

But don’t forget, a photographer working with 35mm film is used to grids: one would make contact sheets of the negatives, and a contact sheet is just that: a grid of images.

BF: In our correspondence, we both shared our fascination for certain tropes of collecting, but also about the idea we share about historical fascination and leisure in the Victorian and Edwardian age as it relates to technology, notably the camera and the social classes associated with its use in leisure-an example being the “Grand Tour” images taken by amateurs of the Middle East and Mediterranean. In Social terms, we can make a quick jump to imperialism and colonialism. The European pre-WWI desire to see distant lands under colonial control and the results in their amateur photography tell a very uncomfortable story of social class, but also the familiarization and disturbing colonial tourism as seen through somewhat naïve amateur images. The fascination that you and I share with these images and the fascination for the operators to make them continue a strange relationship with photography, colonialism and the process of “looking in”. Can you give some of details about your own fascination with images….

BR: The Egypt interest is (at least one place) were your and my collecting habits intersect. I see a clear connection between the rise of photography (end of 19th – beginning of 20th Century) and the ‘great discoveries’ on the back of a sprawling colonial empire. It’s part history, part Indiana Jones, part Poirot… That Edwardian thing appeals to me: the place where leisure / luxury / passion meets (you needed to be well off, and a bit crazy, to lug those bastard cameras around in the African heat.)

It’s a fantasy, obviously, but it’s also the first time that a reality was made ‘available’ to the people who couldn’t afford to travel. Photography made the world a smaller place (for better or for worse).

Instagram is doing the same thing, to this day. We are looking at scantily clad babes who frolic their father’s money away on a beach on the other side of the globe. (I’m taking shortcuts here, but you get the point.)

I’m fascinated by the stereoscopic prints they would sell to tourists to take home. I like postcards from that era, even stamps are revealing. It’s photographic history + postcolonial theory all wrapped up in an interlinked narrative.

Especially the stereographic images (that were extremely popular at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th Century) hold a special power over me. I could bankrupt myself collecting them.

To explain, stereoscopy (or stereo imaging) is a technique for creating or enhancing the illusion of depth. One would look at a card with two offset images separately to the left and right eye of the viewer. These two-dimensional images are then combined in the brain to give the perception of 3D depth.

These stereoscopic prints were loved because they offered a very engaging way to ‘discover’ the wonders of the world for those who couldn’t travel. (Tourism as such did not exists like we know it.). it is telling that they only fell out of grace when cinema started to become more popular. Moving images proved to be even more magical than the 3D still image.

It’s also telling that more than a century later we’re still monkeying around with 3D cinema and VR. Our quest for magical images is still going on.

BF: As a Belgian, I find that position also interesting having read “King Leopold’s Ghost” about the Belgian desire for a colony that became and still relates to the debacle of the Congo. “They chopped off my hands because I carried too much”.

In a way, retroactively collecting these kinds of images have a bizarre postcolonial interrogation about them if you are from the West. Its as if we look for empirical distance through imperial images in an archaeological quest. To unearth the ugly past from a position of privilege is a strange pursuit. Who should pursue this? That is not to be indicting either of us, but it is a strange quest in a way. I can never tell if I am being somehow part of the ugly image’s cycle, which is not the event itself, but the image of the event. How does this work for you and inform your own work…that bizarre patina of historical age….

BR: I am wondering about this as well. At first, my collection started as a way to satisfy my visual curiosity, and as I got further I realized that I was pulling back a piece of the curtain only to reveal the ugly face of Europe’s colonial past.

But on the surface, the things I collect are not ugly at all, quite the contrary, so there is a disconnect between the way our past is represented (beautiful, mysterious, naïve, adventurous, …) and the hardcore reality. This, in itself, is no surprise, we know this, postcolonial theory has been around long enough.

But I’m making money selling art that uses visual markers that are widely recognized but are tainted by blood. That makes me complicit in a tangible way: I can’t go around all academic and say shit like ‘I use palm trees because it allows me to say something about the photographic process without having to explain myself over and over’ and not realize that the reasons why palm trees resonate so much have to do with the way the Western world looks at exotic places in very much the same way colonists looked at them: as places that are to be used (for profit, for leisure) and to be discarded after.

But where does that knowledge leave me? And where does it leave me as an artist? I don’t know yet, I’m trying to find out. At the very least I should be aware of my ‘gaze’ and I should be able to place it in the correct context, historically and morally. And, hopefully, artistically as well.

“Cinema is, after literature, one of my early loves, so it probably plays a big role in the way I work/think/look at the world. And you’re right, when you start repeating an image, but allowing for variations, you get cinema.”

BF: “A Palm Tree is a Palm Tree is a Palm Tree”. The image for Howard’s exhibition of your work shows a typical Roels’ grid, but there is a manifestation at work. From the upper left corner and reading downwards to the bottom right (how does one read a grid?) the palm “becomes” or adversely the other way it grows and disappears? Working with grids presents a certain set of questions outside of the modernist tactics. You are slicing time into strange intervals and in this format it is nearly impossible to distance the idea of cinematic frame from the still composite presented. Does cinema play into your work and how do you pontificate about the dissolve and build up of “time” in the overall grid from their inception as single image?

BR: Cinema is, after literature, one of my early loves, so it probably plays a big role in the way I work/think/look at the world. And you’re right, when you start repeating an image, but allowing for variations, you get cinema.

If you think of it as ‘sequencing images’ or -at a more basic level- ‘sequencing signs’, it’s easier to consider it a form of ‘language’. I construct sentences with images, but because the meaning is not very clear it comes closer to poetry. I am not a poet, and I’m not particularly fond of poetry, but the way I construct/reconstruct these compositions comes close.

Where cinema has a structure in time, a poem also has a structure when printed on a page. It works both moving in time (looking from one print to the other) and standing still (looking at the composition). A bit like a Cy Twombly painting.

The work that you refer to is close to my heart: not only because it’s the first I made for the HGG show, but also because I used pieces of a tropical plant to make photograms. There was no camera involved. Making photograms is also something that the modernist photographers liked to fool around with, and I’m never too impressed with their results. Man Ray is the exception, he called them Rayographs (you have to love him). I called mine “Palmographs”, because that’s what they are, and, let’s face it, Man Ray deserves hat-tips at every turn.

Going back to your question: I have this idea that if I take a box filled with my prints and empty it on the floor, you would get a decent composition. So sometimes I just randomize the process: pick prints at random and assign them to the grid. There’s not always a method to the madness, it’s very much an organic process.

BF: Could you give us some background as to your your linguistic and psychology background? I keep looking over the work and I always see the Rorsarch method surface in your imagery. It is probably due to the use of black and white and “mirroring” images. So, this creates a psycho-analytical space in which I enter the proverbial “terrordome” of image free association. A Palm tree is a palm tree until it’s a fist, no? I would be intrigued to know if you also have a background with psychoanalytical theory or if perhaps I am encroaching the linguistic territory with the notion?

BR: to me, psychology and linguistics go hand in hand. But while I think about language consciously, I don’t dwell on the psychology of my images. I just let them happen. I am, however, very interested in the intersection between neurology and the way humans assign meaning to images / icons. Which is also the basis for the Rorsarch test as it happens.

My next book will be called ‘The Pyramids And Palm Trees Test’, which is also a title of an existing medical test that determines the degree to which a subject can access meaning from pictures and words. The test is used to check for aphasia, visual agnosia or general semantic impairment (i.e., Alzheimer’s disease).

The idea of the test is simple: researchers show the test subjects a picture of a palm tree and of a Canadian fir and they ask what image fits best with a pyramid. (They have a whole series of these questions: does a bat fit best with a) an owl or b) a pigeon? Does a match box fit best with a) a candle or b) a light bulb?)

Some images are so iconographic that they are deeply embedded in our thinking. Form and meaning go hand in hand. When the test subjects cannot make the right connection, it means there’s something wrong with the language center of their brain.

This test was a huge discovery for me, because it made me realize that neurologists think about iconographic images in the same way I think about them. What’s more, they use them in the same way.

BF: “Yucca as a Sumerian Script” (2018). This is one of my favorite pieces that I have seen from you. I feel there is a bit of a breakthrough happening in the work. Having studied the work of both Harry Callahan and Ray Metzger in the past, I was struck by how this work is somehow an elevation of a post-Bauahaus (Chicago version) aesthetic in which the language of shadow, light and contrast become a new language. Metzger was really strong at creating these images that used the grid of street scenes in such a way that the distortion of repetition, abstracted along with pushing the contrast created a new image. I guess it was a mosaic effect. In the Yucca piece, you are now making a direct correlation to Sumerian tablets, scribes and the “strike form” of the hammer on the surface of the tablet. It is asking the viewer to see language in nature, but also to process historical moments. On top of that the Yucca references the new world in popular consciousness as it is associated (freely) with Joshua Tree. So, there are several levels outside of the image of the subject itself. The strike form, almost like a Lucio Fontana razor cut reverberate the idea of the hammer. Is this a direction that you are going to pursue, to simultaneously strip down the visual language and let the text do more of the work? I would be fascinated to see where this goes. In reduction, I feel there is more to say…

BR: The Yucca pieces try to answer the question: ‘what happens when you deconstruct an iconic image?’ A yucca plant is widely recognized, so what happens when I reduce the information? The real challenge is that I need to make a mask in the dark room to print these little triangles: I take a photo of a Yucca plant and organize it so that I only print the top of the leaf. But because I do this in the dark I have no real idea what I’m doing until I develop the print.

What I end up with is random and reduced and abstract. Sometimes deconstruction means death, in the Yucca pieces it means something else: the reduced signs (the small parts of the paper that were exposed) come alive.

Like a language that we can’t understand but carries some meaning. Sumerian script is also called ‘cuneiform script’ which in itself simply means “wedge shaped”, exactly like the tip of these yucca leaves.

And like Fontana cut through the canvas, or like a scribe uses a reed to write in a clay tablet, I use the negatives to stamp light on the gelatin silver paper. White becomes dark, and dark becomes meaning.

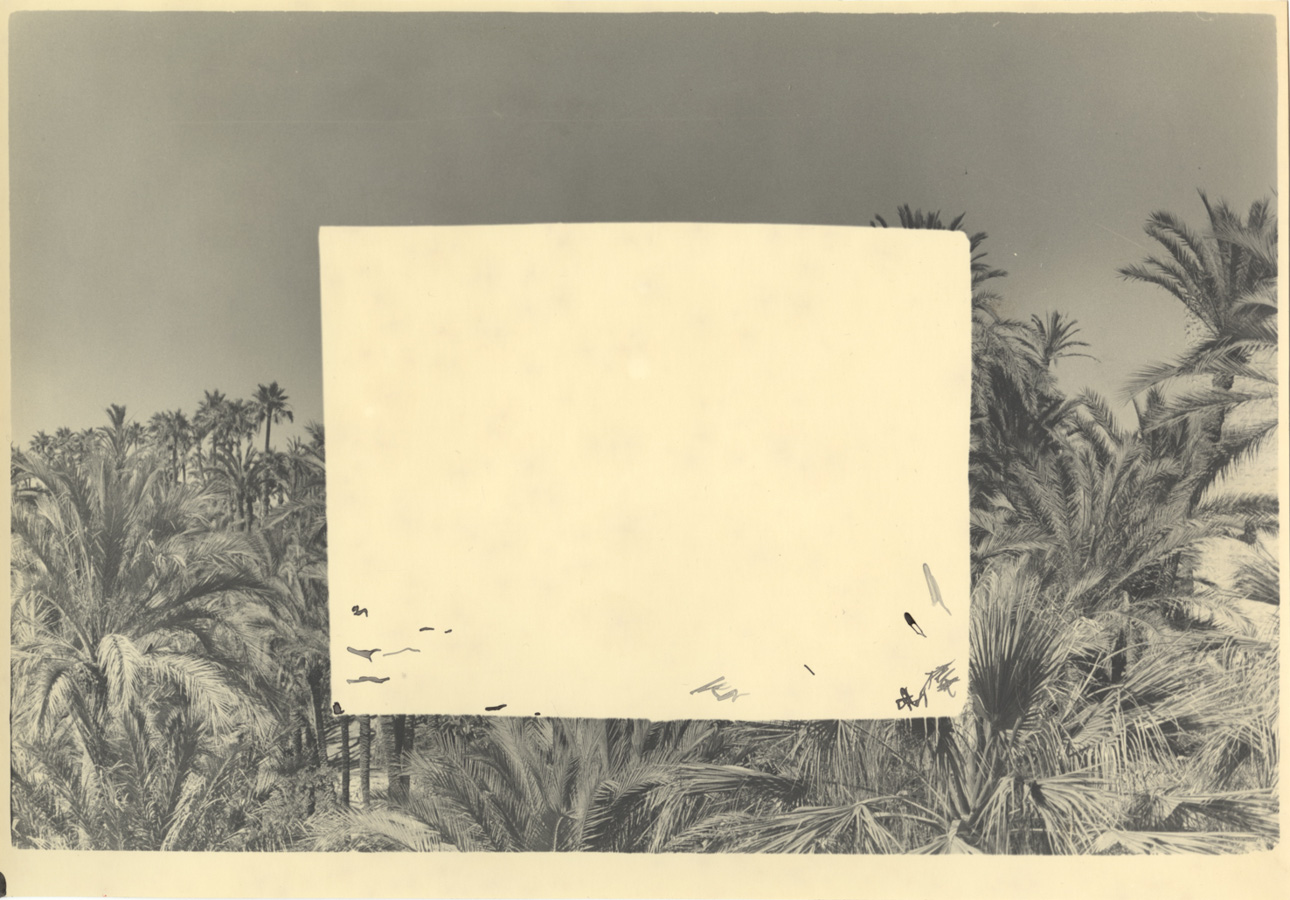

BF: A number of your prints have drawings or paintings across the surface in India ink. It is a synthesis between hand-made and repetition. So, the aura or lack of the mechanically produced against the singular drawn image in which the author is extremely present. As a strategy, do you see yourself working more or less with this method in the future?

BR: More! It started out with a way to break away from the repetition of doing repetitions. It’s a game I play with myself: “Can I add anything to this image?” “Should I add anything to this image?” It’s less ‘easy going’ than it looks because I am too lazy to make a print again when the fooling around with black Indian ink goes awry. Indian ink is unforgiving: when I mess up, it’s going to be properly messed up, there’s no walking back from it. I like that stress, and if I’m not convinced it’s going to turn out okay, I’m better off leaving the print alone. This being said: there’s a long tradition of photographers retouching their prints with ink, it’s the only way to get rid of the little blemishes that always occur in analogue gelatin silver prints (dust, little scratches…) so the use of Indian ink doesn’t feel inappropriate.

Bruno V. Roels: A Palm Tree is a Palm Tree is a Palm Tree is showing at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York and runs from March 22 to May 5, 2018.

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm. Images @ Bruno V. Roels.)