By Masashi Kohara

Who is Takuma Nakahira? A photographer of the bure, boke1 style. A member of the Provoke group. An essayist and photography critic, a political activist, a photographer who talked too much, a photographer who lost his memory, a photographer who forgot his mother tongue, a legend… Takuma Nakahira, who influenced many photographers of the subsequent generation with his radical language and his pictures, suddenly fell ill in 1977 and is now regarded as a legendary figure in the world of photography.

Nakahira was editor of a magazine of the New Left in 1963 when he met the photographer Shomei Tomatsu and, as a result of this meeting, switched to photography himself. Through Tomatsu he made friends with Daido Moriyama, who initiated him in the techniques of shooting and developing and quickly drew him under the spell of photography. In 1968 he founded Provoke magazine with the critic Koji Taki, the poet Takahiko Okada, and the photographer Yutaka Takanashi; encouraged by Nakahira, Daido Moriyama also became a member as of the second issue. In their joint manifesto they called for a liberation from photography that merely illustrated preconceived meanings, thus provoking »a language to come (thought). At this time, Japan was in the middle of an economic upturn. At the same time, however, people were losing confidence in the established systems and values, and the call for social change reached its climax. Contrary to the prevailing photography of social realism, based upon a theory of alienation that was founded on simple contrasts, the Provoke photographers campaigned against a world of seeming certainty and ceased to ask “What should we photograph?” or “How should we photograph?”, instead asking more fundamental questions such as “What is photography?”, “Who becomes a photographer?” or “What is seeing?”. Their characteristic grainy, blurry, shaky pictures are the photographic expression of their doubt about a photography that amounts to illustrating a self-enclosed aesthetics or language. They are a conclusive reflection of a time whose contours are slowly dissolving. They are attempts not to »shoot« the pictures actively, but rather to allow the pictures to develop on the basis of a deliberately passive stance, with the frequent use of wide-angle lenses and no-finder technique, and thus to rehabilitate the unruly nature (the independent action) of the camera that lies hidden in the concept of »expression«. By reflecting the difference between their own eye and the eye of the camera in the photos in an extreme manner, the Provoke photographers were in search of a way of capturing the form of the world that was eluding them.

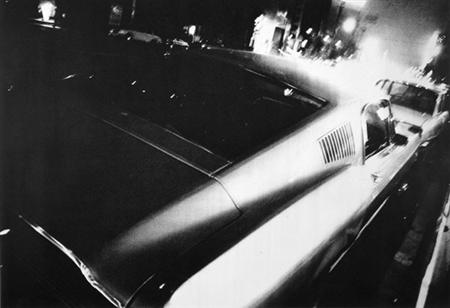

In the final phase of Provoke magazine, that existed for a mere year and a half, Nakahira collected scenes from illuminated night-time cities that elude language, and published them in the book of photos For a Language to Come in 1970. The pictures, that convey an urgent sense of capturing the naked world outside of language or consciousness, were presumably intended to depict an anonymous mediator who allows the individual viewer to discover a »direct language« (a language to come). A few years later, Nakahira rejected his entire work wholesale in Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?. His lyrical black-and-white photos, he maintained, failed to initiate the communication he had intended, instead placing the world in the framework of his personal visions and imposing them on the viewer. Photography, he claimed, was essentially a result of an interplay of things, thoughts and the self. In order to confront the world directly and to allow things to speak as things, he therefore felt it necessary to systematize the idea of things, the view of things. After repeating such phrases several times, Nakahira presented his draft of a photography to come, colour photos that had been divested of any kind of personal touch. He rejected any kind of nuance and any emotion and defined his method of stringing together images as in a lexicon, whose most important purpose consists in clearly expressing its particular object«. He announced that he aimed to reject all meanings and images stored a priori in his consciousness and to return to the starting point of the photographic apparatus, where the only thing captured is the light emanating from things. Finally, he even burnt most of his pictures and negatives. For Nakahira, plants are uncanny, mysterious creatures. He sees in them transcendental beings that are removed from the world of seeming certainty, that carry the otherness of things within them, and that threaten the self with their silence. To him, plants with their autonomous growth imply an intermediate state that belongs neither to the subject nor to the object of perception.

In an attempt to revolt against the self in the activity of photography, Nakahira desperately sought to find a direct language. But as he himself admitted, he felt blocked by his own essay “Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?” in the mid-1970s and finally slid into a severe crisis as a photographer. In his hopeless effort to destroy the sphere of self-awareness, to overcome the gaol of consciousness, by becoming conscious of consciousness, he reached a dead end. His botanical dictionary was thus like a voyage that was destined to run aground from the outset. At this point, the photography of Nakahira’s group, that was intended radically to break away from institutionalised visual habits, became recognised as the bure, boke style1, although this label caused it to lose its initial potency. At a time when the media were beginning, here and there, to broadcast the Vietnam War or the Palestinians’ fight for independence, Nakahira hesitated to push the release. He was inhibited by his anger that photography lacked the power to change the world directly and that it was powerless in the face of invisible things, while nevertheless lending power to the subject looking through the viewfinder. While Nakahira was coming up against his limits as a photographer, like a man possessed he continued to ask himself what photography is, attempting to get back to photography with the aid of appropriate writings. However, in 1977 he suffered acute alcohol poisoning, thereby losing much of his memory and command of language, his most important weapon.

“August 1, I woke up at 6:31 a.m., I went to the loo, set my watch, that was a bit fast, by the speaking clock, came back at 6:53 a.m. Couldn’t get back to sleep at all afterwards. Sobriety as of around 6:31 a.m.” 2

When Nakahira recounts his own activities in his Photographic Diary – for example the fact that he set his watch – he thereby defends himself against a state that is constantly confronting him with the abyss of oblivion. At this time, Nakahira had to keep transitory things alive with the aid of his diary and photographs so as not to lose touch with the outside world.

Degree Zero – Yokohama #18, 2002

Degree Zero – Yokohama #18, 2002

Degree Zero – Yokohama #73, 1999

Degree Zero – Yokohama #73, 1999

A New Gaze (1983) contains the photos he took in the course of his recovery lasting several years. They are banal, everyday themes, as you would find in any other peripheral urban area. But although they do not portray anything special, there is something disconcerting about the scenes, like the scene of a crime. It is probably the unfathomable emptiness that unnerves the viewer. In these pictures, the natural cycle of meanings is interrupted, and the code for deciphering the world is only weak; they merely point at things like small children. The uncertainty that they cause is the fundamental effect triggered by the photography medium per se. Photography manifests itself in these pictures in its primal unruliness. Because it is a message without a code, offering no meaning of its own volition, the viewer looks for a clue (a title) in order to read something in its surface. The pictures contained in the collection in A New Gaze have a strangely tactile sense of living about them; a view is burnt into them that differs from the world familiar to us. We could refer to them as a lifeless copy of the world, a death mask that, although it is the cast of the dead face of a familiar person, has an uncanny effect. What Freud termed das Unheimliche (the uncanny), is an experience that shakes us by reproducing something once familiar to us, but now repressed, in an unknown, alienated form. But what about the perception of a person who forgets even everyday things or even the names of members of his family? Wandering about, robbed of all familiar features, his mind slips through the weak lines that people have drawn, falling into a confusing world flooded with light… It is, in any case, a world that needs to be understood not with the eyes but rather by touch; any attempt to control things that structure the world with one’s own will is doomed to fail. Only when the »world of seeming certainty collapses does it become clear how full of violence and unfoundedness the world is. I went through with my photos, firmly convinced that the plain, in a sense elementary, act of photography consisted in capturing the object very clearly, Nakahira writes in the epilogue of his book of photos. But by seeing the world through new eyes where his self-awareness had failed, and capturing its materialistic cruelty by the elementary act of photography, he was able to find an approach to photography itself. Even if he found the world that was full of uncanny things, sickening, Nakahira became a photographer once again by deciding to stare at it through the lens. The camera as an anti-interpretative device that captures everything in front of it without understanding it, as a remedy for memory loss that accepts every detail without difference – this camera became Nakahira’s third eye. And so he embarked on a journey to re-establish his sundered link to the world – without language as a filtering device, but with the camera as a gathering apparatus. “My photography is an absolute necessity for me, having forgotten everything.” This statement put Nakahira on a level where photography (capturing, seeing) and life are synonymous.

“I believe that photography is neither creation nor memory, but documents. The act of shooting a photograph is not something abstract. It is always concrete. No manipulation to make simple things complicated through conceptualization. Only the real I encountered through the medium of the camera is here in my photographs.” 3

In recent years, Nakahira has switched completely from black-and-white to colour photography, and since falling ill more than twenty years ago he has continuously taken photographs in the style of a diarist. When he would leave his house to take photos, immediately after being released from hospital, when he no longer knew where he had come from, and could not even cross a road at traffic lights, he felt like a nutshell drifting on the ocean. But a river that runs past his house in Yokohama served as a visible meridian, and a red-and-white striped tower that you could see upstream on the left bank became his lighthouse, on the basis of which he would determine his position. Nakahira’s photographic activity resembled drawing a map, proceeding on the basis of a line (the river) and his home (Heim) on the white surface. It seems as if he was turning the uncanny (das Unheimliche) that filled the outside world into the homy (das Heimliche). The gesture with which he gathered familiar things around him and his confrontation with that which threatened him – both dwell under one roof. For more than twenty years, Nakahira has been roaming around every corner in the vicinity of his house and the roads in which he used to live. And every time he goes out he takes photos of the same objects in the same places. It is as if he just happens to follow his own footsteps. But for him, the world appears with a virginal new face every single day. This face is recognized only once, over and over again only once, in the »here and now.

Seeing the world as a face. This does not mean personifying objects but rather confronting them with the same immediacy with which we understand other people’s faces. The face, the immediate, direct surface that may not be resolved in terms of form and meaning. Nakahira’s recent work opposes the magnetic maelstrom of generalization and standardization that is based upon an ossified language. It exists as an outer layer, that points to the world in the face of the this. The world is captured not in abstraction but rather visible things are liberated in their concreteness. The objects lost in the abstract are revived in the view of the concrete. And this takes place with an openness verging on brutality. For example, this snake differs from that in terms of their momentary unique state. What Nakahira’s recent work shows is nothing that might be described by a general substantive, but rather merely this snake. In other words, the snake that you saw in that place at that time and the snake that you see in this place at this time, are not the same, but are rather conceived as something unique and incomparable every single time. The camera’s mechanical eye focuses on this subtle moment as a photographic face. To be even more precise, we should not talk about a this, but rather a none other than this. None other than this implies the possibility that this may have been something else at one time, but it is nevertheless about the coincidental nature of an “only this” in itself. This means that it is about the complexity that exists in none other than this that contains every other none other than these, that is to say, an openness that may contain every other latent coincidences. And this exists only to the extent that it calls none other than I by its name.

“This is it! That is it! These photographs I make public here are from my conclusion about photography for the moment!” 4

A lexicon that gathers together this cat, this tree, this bird, this tower, this fire, this person. Without a doubt, these are all things that Nakahira actually encountered himself, that make up his reality, and that, as such, have acquired meaning for him. The lexicon, as featured in his recent works, presents the world of the “here and now” that shuts itself off from any generalization. This “dictionary” thus eludes the conventional form, in which individual things are found in relations harmonized with each other and ordered according to concepts. It is a paradoxical surface on which every meaning is immediately sucked up by a void the very moment it comes into being, and that forms both the tautological inner essence of language (“this is this”) and its outer surface. The “none other than this” illustrates with destructive force all ideas that seek to lodge themselves in abstract concepts. Its form hinges decisively on its being recognised as something coincidental. It is a lexicon of events, as Nakahira once imagined it, hinting at it as a possibility in Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?. Without any kind of system or standardization, it is a lexicon that consists solely in the process of gradual accumulation, a documentation of someone who was once perhaps someone else, and yet no one else but I. As a direct record of the life of a photographer, it combines the reality chosen by this “no one else but me” with the reality of “someone else who is no one but himself”. It projects the “second reality” (photography), transformed into an anonymous mediator, onto the reality of the viewer, thus provoking language and life. Nakahira used to refer to the events that this entails as a language to come. But what do we see in Takuma Nakahira’s photography, what reality do we choose?

(Translation: Richard Watts)

1 »bure, boke« describes a style in Japanese photography at that time that was characterised by shaky pictures, out-of-focus perspectives, and blurred focusing: bure (blurred), boke (out of focus) [note by the editors].

2 Takuma Nakahira in the »Photographic Diary« in A New Gaze [Arata naru gyoshi].

3 Takuma Nakahira in: Degree Zero – Yokohama, exhibition catalogue, Tokyo: Osiris 2003.

4 Takuma Nakahira on the exhibition »Why an Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Humans and Animals?«[Naze hoka naranu ningen = dobutsu zukanka], Shugoarts, Tokyo 2004.

(Camera Austria 91/2005, page 9 – 20)

ASX CHANNEL: Takuma Nakahira

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow ASX on Twitter.

For inquiries, please contact American Suburb X at: info@americansuburbx.com.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher

.jpg)