“I devised my own way of working. With a flash-mounted medium-format camera around my neck, I would spend long hours staked out at overlooks, looking to match up just the right person or couple or group with just the right background––always searching for that particular elusive “something” that constitutes a compelling image.”

By Roger Minick, 2012

My interest in photographing sightseers began back in 1976 when I was invited to teach at the Ansel Adams Workshops in Yosemite National Park. I vividly remember how all the photography students would gather at the famous Inspiration Point overlook, get into position with their cameras mounted to tripods, and wait for the grand man himself to move along the line bestowing his blessings on each student’s composition and choice of exposure. A cacophony of clicking shutters would then follow, with the result of course that all the students ended up making nearly identical images. It wasn’t long, however, before I became aware of something else going on at the overlook: waves of tourists were continually arriving at the overlook’s parking lot in cars, buses and motorhomes, thrusting their way through this gauntlet of photographers not only for a clear view of the famous vista but also for the obligatory snapshot of themselves proving they were there. After witnessing this recurring bit of theater over several days, I found myself becoming increasingly fascinated with these visitors, recognizing what a striking cross section of humanity they were. I began to see the visitors as having a specific humanity, their own classification, a genus––Sightseer Americanus, if you will. Previously in my photographic career, when my projects took me into the landscape, I had tended to look on sightseers with disdain, and certainly had never considered them a “subject” I would want to photograph seriously. Yet over the course of those days I began to feel I was witnessing something uniquely American, something that I suddenly very much wanted to photograph.

Three years later, I finally set out with my wife Joyce Perrin in our VW camper on a road trip around the western United States, with the sole purpose of photographing sightseers. During that first trip I photographed in black and white, and though I felt excited about the images I was getting, it was not until I returned to my darkroom and began to make prints that I realized something was missing. I soon realized that the irony and humor I had seen in the vivid colors of the people’s dress juxtaposed against the surrounding landscape, with its infinite palette, was getting lost in black and white.

I immediately decided I must work in color. So the following year we retraced our route from the year before, and even prior to seeing a single print from that trip I knew that changing to color was the correct decision.

“When I approached people for a portrait, I tried to make my request clear and to the point, making it clear that I was not trying to sell them anything. I explained that my wife and I were traveling around the country visiting most of the major tourist destinations so that I could photograph the activity of sightseeing.”

During the years I worked on the Sightseer Series, I devised my own way of working. With a flash-mounted medium-format camera around my neck, I would spend long hours staked out at overlooks, looking to match up just the right person or couple or group with just the right background––always searching for that particular elusive “something” that constitutes a compelling image. Sometimes it was simply the style of clothing or the colors people chose to wear that caught my attention. Sometimes it was their mode of travel or the things they brought with them––their cameras, cell phones, radios, binoculars, strollers, pets––that attracted me. Often I was attracted to the interaction within a group, hoping I could somehow capture a certain family dynamic on film. (Over time I even came up with theories based on my observations––my favorite: those families who were the best color-coordinated seemed to get along the best!)

When I approached people for a portrait, I tried to make my request clear and to the point, making it clear that I was not trying to sell them anything. I explained that my wife and I were traveling around the country visiting most of the major tourist destinations so that I could photograph the activity of sightseeing. I would quickly add that I hoped the project would have cultural value and might be seen in years to come as a kind of time capsule of what Americans looked like at the end of the Twentieth Century; at which, to my surprise, I would see people often begin to nod their heads as if they knew what I was talking about. I would then offer them a free portrait of themselves in front of whatever they had come to see, using a Polaroid camera I also had strapped around my neck. Once I had their permission, I went to work quickly, having learned that sightseers are on a tight schedule, are tired and exhausted from miles and miles of travel, and so had little patience for lots of photos. In fact, I generally felt lucky if I was able to get off three exposures in one session. If people were in a chatty mood or seemed to be particularly at ease, my encounters might last longer, but in most cases I made my portraits within a matter of minutes. Although I instigated most of the portrait sessions, there were times when the portraits came about on their own, such as when visiting tourists might ask me to take a picture with their camera so that everyone in their family or group could be included. I would gladly accommodate, of course, and if I sensed a possible portrait for my series, I would then ask if I might be able to take a picture of them with my camera.

As I have already suggested, my technical approach to the portraits was simple and straight forward. For one thing, I hand-held the camera, which allowed me more spontaneity. Also, I chose to use 400 ASA film, which gave me a fast shutter speed for maximum depth of field. As I had done with the black and white work the year before, I used an on-camera flash, setting it to give me just the right amount of “fill light” to light faces in mid-day sun, so that eyes didn’t become lost to shadows under hat brims. The use of flash had another advantage: I could make it equalize foreground light with background light, which often gave a false-backdrop or diorama look to the photograph, an effect that I grew to like enormously. As for how I posed the people, I was greatly inspired by the simple snapshot, having always been fascinated by its directness and unpretentious simplicity.

“In the end I came to believe that there was something more meaningful going on––something stronger and more compelling, something that seemed almost woven into the fabric of the American psyche.”

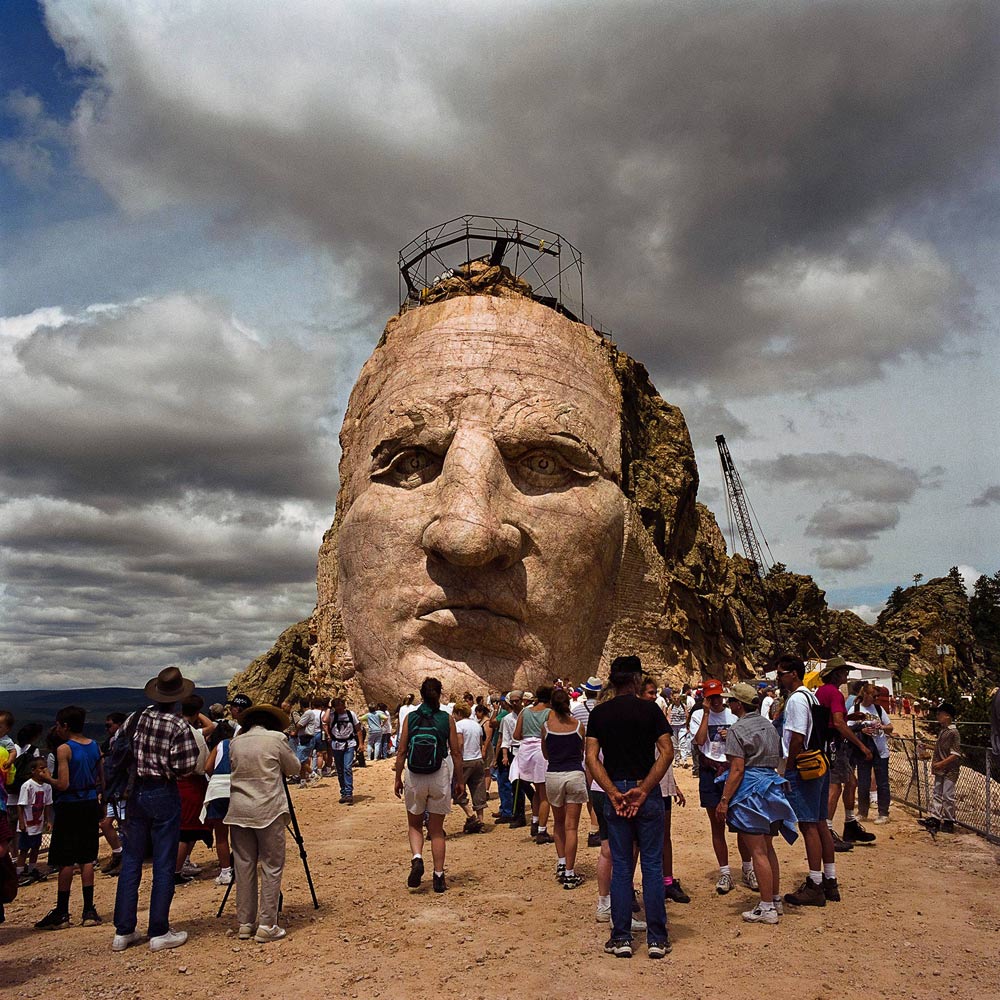

After the two color sightseer trips in 1980 and 1981, I worked on several other photographic projects before returning in the late 1990s to complete the project, expanding it to include sites in the Midwest and East. Throughout my hours of driving and time spent at hundreds of overlooks––from Yosemite National Park to the Blue Ridge Mountains, from Old Faithful Geyser to the rim of the Grand Canyon, from Niagara Falls to the St. Louis Arch, from the Crazy Horse Memorial to the World Trade Center, from The Alamo to the Washington Mall, from Zion Canyon National Park to the Great Smoky Mountains––there was one question that continued to press upon me for an answer. What was it that motivated people, by the hundreds of thousands, at great expense of time, money, and effort, to visit these far-off places of wonder and curiosity? I must confess that there were times in my travels, squeezed elbow-to-elbow with my fellow travelers, that I viewed their presence at the overlooks as nothing more than another example of mindless, boorish, behavior. I thought they were there simply to get their pictures taken as quickly as possible, the one tangible validation of their trip, and then head on to the next overlook, the next campground, motel, bus stop, then home––the experience at any one of the dozens of overlooks remembered only later through a snapshot they barely recalled taking.

But in the end I came to believe that there was something more meaningful going on––something stronger and more compelling, something that seemed almost woven into the fabric of the American psyche. I would witness this most dramatically when I watched first-timers arrive at a particularly spectacular overlook and see their expressions become instantly awestruck at this their first sighting of some iconic beauty or curiosity or wonder. After seeing this happen innumerable times, I began to compare what I was seeing to the religious pilgrimages of the Middle East and Asia, where the pilgrims are not just making a trip to make a trip, or simply to return home with some tangible piece of evidence that they were there––the snapshot––they have instead come seeking something deeper, beyond themselves, and are finding it in this moment of visitation. For as with all pilgrimages, they have made the journey, they have arrived, and are now experiencing the quickening sense of recognition and affirmation, that universal sense of a shared past and present, and, with any luck, a shared future.

http://sightseerseries.com/

(all images © Roger Minick)