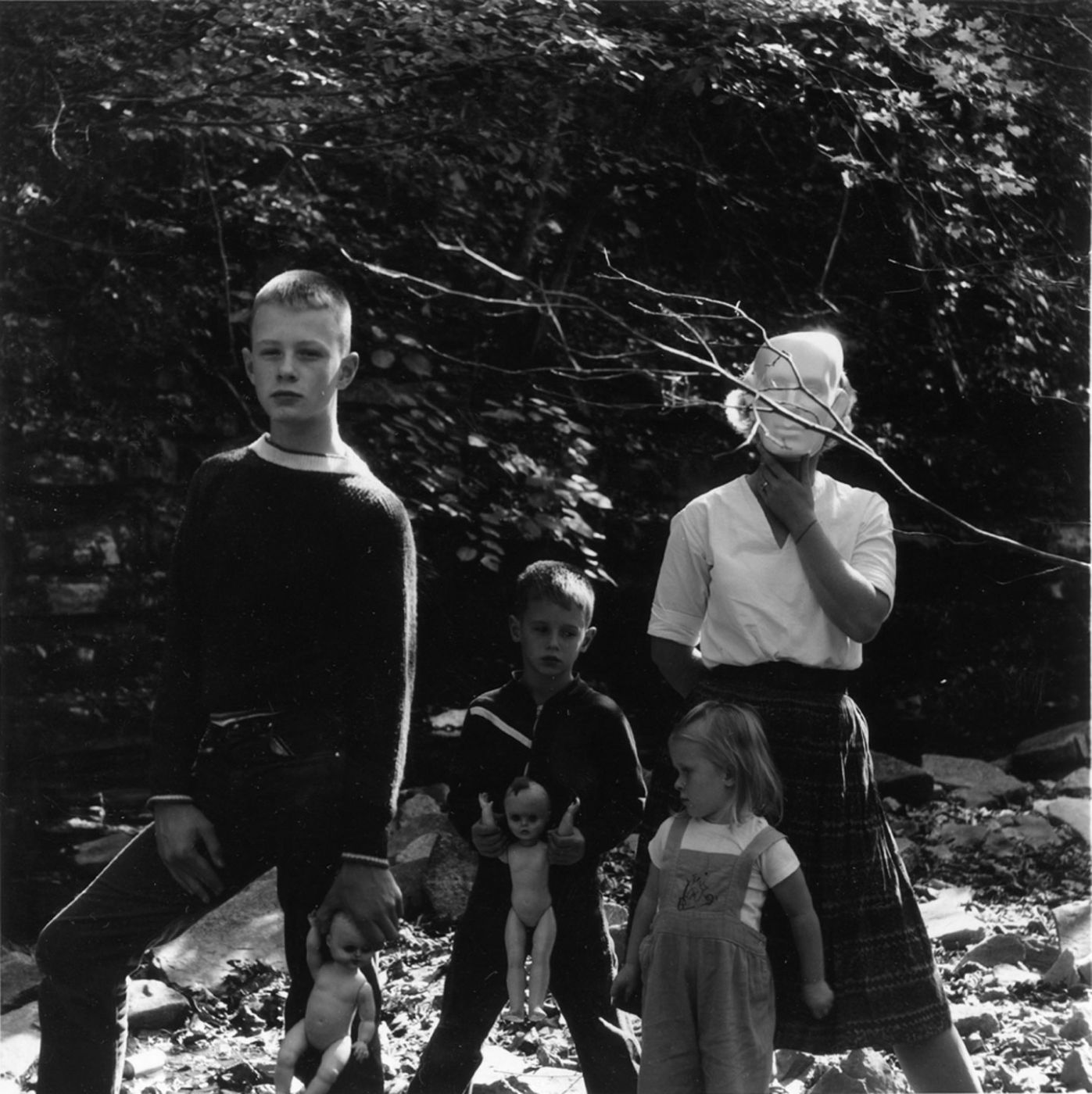

Williams wrote me that there was a photographer there who took pictures of children and American flags in attics.

Excerpt from The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays

By Guy Davenport

When I moved to Lexington in 1964 the poet Jonathan Williams wrote me that there was a photographer there who took pictures of children and American flags in attics. His name was Ralph Eugene Meatyard. He was, Jonathan insisted, strange. I had learned to trust Jonathan’s judgments. When he said strange, he meant strange.

The next time Jonathan was in town, one of one his reading and slide-showing tours around the Republic in his Volkswagen, The Blue Rider, with its football decal on a window saying THE POETS (the football team of of Sidney Lanier High School in the pine fastness of Georgia), he and Ronald Johnson, Stan Brakhage and his six-year-old daughter Crystal, Bonnie Jean Cox and I set out to visit the Meatyards. The address was 418 Kingsway. We all piled out at 418 Queensway, and to this day I don’t know the startled citizens who opened their door to find such a collection of people on the steps. Jonathan was got up as a Methodist minister in a three-piece suit, Stan was in his period of looking like a Pony Express scout out of Frederic Remington, and Bonnie Jean and Crystal were both gazing innocently up out from under bangs.

We fitted in well enough at the Meatyards’ when we got there, a place where you were liable to find anything at all. There was an original drawing of Andy Gump crying “Oh, Min!” from a toilet stool: he has no paper. There were Merzbilden, paintings by the children, found objects, cats and dogs, books jammed into every conceivable space.

Gene Meatyard was a smiling, affable man of middle age and height. His wife Madelyn, Scandinavian in her beauty, had a full measure of Midwestern hospitality to make us feel comfortable. My own welcome was assured when we heard, as Melissa, the youngest Meatyard, showed her agemate Crystal Brakhage, the kitchen, a little girl’s piping voice saying, “Guy Davenport has ants and bugs in his kitchen.” This gave me a chance to explain that I kept a saucer of sugar water for the wasps, hornets and ants that I liked to see in the house. To the Meatyard’s it meant that I couldn’t be all bad.

Photographs were handed around. We talked about them. But not Gene. For nine years I would see the new pictures as they were printed and mounted, always in complete silence from Gene. He never instructed one how to see, or how to interpret the pictures, or what he might have intended. The room was full of keen eyes: Jonathan’s lyric, bawdy eye; Ronald’s eye for mystery; Stan’s cinematic eye (a bit impatient with still images, as Gene was impatient with Stan’s films – he never went to the movies, but would watch television if the program were sufficiently absurd); Bonnie Jean’s stubborn, no-nonsense eye.

He developed his film only once a year; he didn’t want to be tyrannized by impatience…

I did not know until after his death that he brought me the pictures to cheer himself up. “Guy knows what to say,” he told Madelyn. I only said what the pictures drew out. I think he liked my having to fall back on analogies: that this print had a touch of Kafka, this a passage as if by Cezanne, this echoed de Chirico. In his last period he was fascinated by Cezanne and the cubists, by the verbal collages of William Carlos Williams.

We saw a wealth of pictures that evening. I remember thinking that here was a photographer who might illustrate the ghost stories of Henry James, a photographer who got many of his best effects by introducing exactly the right touch of the unusual into an authentically banal American unsualness. So much of Gene’s work requires the deeper attention which shows you that in a quite handsome picture of lawns and trees there are bricks floating in the air (they have been tied to branches to make them grow level; you cannot see the wires).

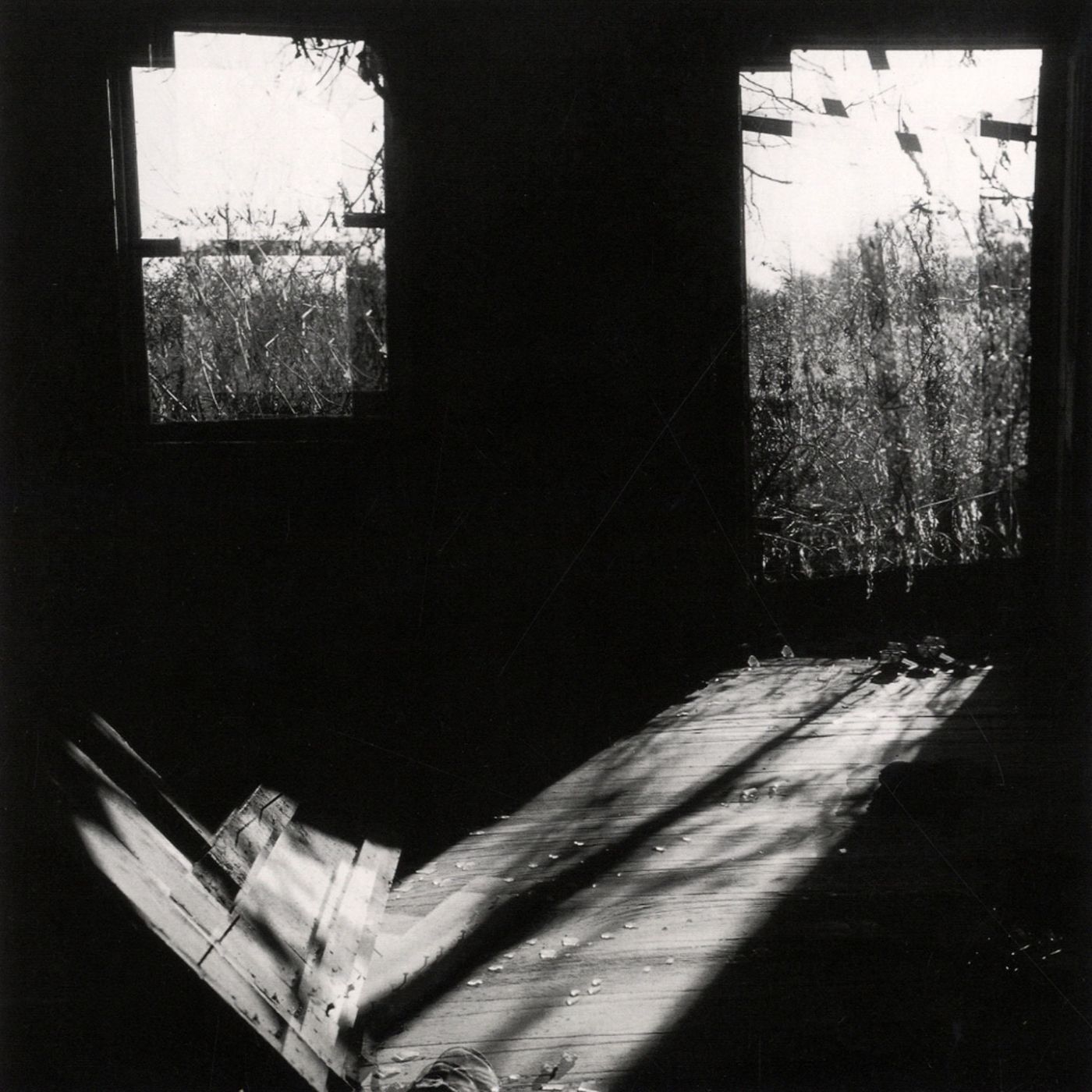

Light as it falls from the sun onto our random world defines everything perceptible to the eye by constant accident, relentlessly changing. A splendid spot of light on a fence is gone in a matter of seconds. A tone of light is frailer in essence than a whiff of roses. I have watched Gene all of a day wandering around in the ruined Whitehall photographing as diligently as if he were a newsreel cameraman in a battle. The old house was as quiet and still as eternity itself; to Gene it was as ephemeral in its shift of light and shade as a fitful moth.

He developed his film only once a year; he didn’t want to be tyrannized by impatience; and I suspect that he didn’t like being cooped up in the darkroom. He was a lens grinder by profession, which meant he was short of free time. His evenings were apt to be taken up with teaching, lecturing, arranging shows, and he longed to read more and more. There were books in his automobile, by his equipment in his office. He had more hobbies than could be kept up with, especially those that involved his family; hiking, cooking, collecting the poetic trash that served as props for his pictures. One could usually find the Meatyards up to something rich and strange: making violet jam (or some other sufficiently unlikely flavor), model ships, fanciful book covers; listening to a superb collection of antique jazz, or to recordings which Gene seemed to dream up and then command the existence of, like the Andrews sisters singing Poe’s “Raven” (“Ulalume” on the flip side, both in close harmony). He had a recording of the wedding of Sister Rosetta Tharp. He has a loose-leaf notebook of thousands of grotesque and absurd names. He was a living encyclopedia of bizarre accidents and Kentucky locutions. One evening he turned up to tell with delight of hearing an old man say of the moving pictures these days that by God you can see the actors’ genitrotties.

And there was nothing behind him, nothing at all that once could make out. He had invented himself, with his family’s full cooperation. One knew that he had been born in Normal, Illinois, because of the name. He had a brother, an artist, but it took forever to find this out. He had been to Williams. Williams! Surely this was an invention. Like hearing Harpo Marx had a degree from the Sorbonne. For whereas Gene seemed to read German, he pronounced French like Dr. Johnson – as if it were English. Greek nor Latin had he, though he once figured out with a modern Greek dictionary that a lyric of Sappho (which he had set out to read as his first excursion into the classics) had something to do with a truck crossing a bridge. Yet, by golly, he had been to Williams College. He was there with the Navy V-12 program. One even learned that he used to play golf. But he had no past. His own past had no interest whatever for him. Tomorrow morning was his great interest.

Continue reading here:

The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays

ASX CHANNEL: RALPH EUGENE MEATYARD

(All rights reserved. Text @ Guy Davenport, Images @ Meatyard Estate)