Sergei Vasiliev

Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopedia Print No.12

2010

Giclée print

165 x 112 cm

©Sergei Vasiliev, 2010

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

By Laetitia Martinez & David Price, ASX UK, March 2013

Walking through affluent Sloane Square into the stately building that houses the Saatchi Gallery, directly into the opening salvo of GAIETY IS THE MOST OUTSTANDING FEATURE OF THE SOVIET UNION: Art from Russia is a visceral experience.

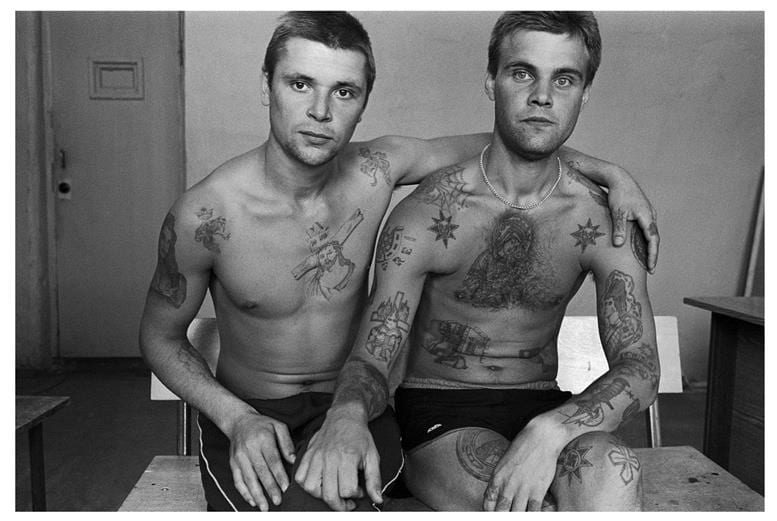

Sergei Vasiliev’s large scale monochrome series of heavily tattooed Russian prisoners is an ensemble of shock-and-awe rawness with its depictions of haunted eyes, scarred, broken faces and stumps of amputated fingers, proudly displayed like a child who just lost his first baby tooth. However, among the thousand yard stares and improvised piss, blood and septic ink tattoos of Stalin, religious icons, naive Disneyland-style Kremlins, skulls and pinup girls, there emerges a dignity that elevates the subjects to near saintliness. In one particular image, a prisoner gazes upwards in seemingly divine rapture, adorned by an inky crown of thorns, albeit with “Gott Mit Uns”, a Nazi battle cry, inscribed across his chest.

Also surprising is the tenderness that we encounter between these men, the intimacy of their poses often betraying a fraternal bond entirely at odds with their primal, brutal demeanours. In one shot we see two men that look so alike they could be brothers, sitting closely together on a bunk, their body language suggesting the kind of intimacy shared by a long-married couple, one hand resting casually on the others knee.

When considering that Vasiliev, a prison warden himself, began this series not as an artistic endeavour but simply to create, at the request of the KGB, an objective document of the tattoo language prisoners used as a coded means of communication with each other, the aesthetic value of the work becomes even more fascinating, not only as a socio-historical document, but also in asserting that photography can be amorphous in nature, as illustrated here through Vasilev’s re-appropriation of images originally intended as an anthropological, political archive. When presented in a gallery context, they become a visceral work of art, one which ironically acts as a potent symbol of individual freedom of expression on the part of both Vasiliev and his subjects.

Sergei Vasiliev

Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopedia Print No.4

2010

Giclée print

112 x 165 cm

©Sergei Vasiliev, 2010

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

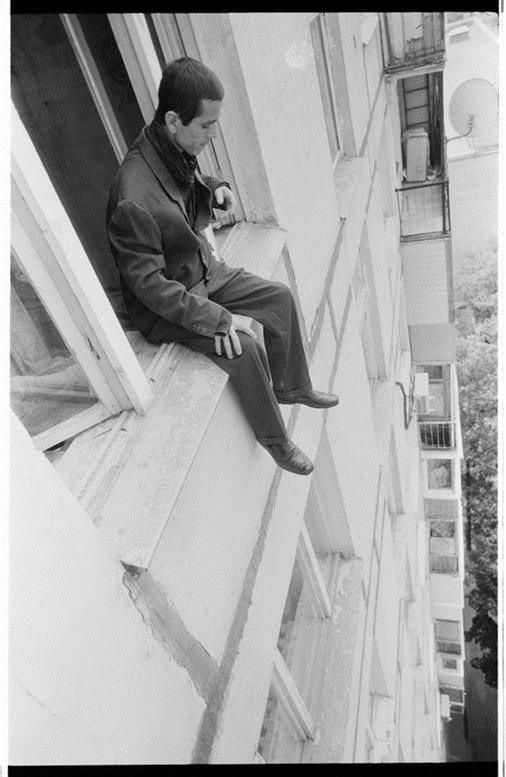

Vikenti Nilin continues this sense of the body as a mirror of the machinery of The State, a disposable vessel that is devoid of the democratic western body politic and renders it as part of the cannibalistic Soviet apparatus. Some of those that were not swallowed by old school communism can now be found in Nilin’s large monochrome corpus The Neighbours, perched on the window ledges and balconies of brutalist tower blocks like shabby birds of prey who dropped their hammers and sickles. By composing in harsh, oblique angles from a birds eye perspective, Nilin accentuates the precarious nature of the subjects pose. Despite the delicate equilibrium the subjects are exposed to, they appear relaxed, almost hypnotised by the trees below, with no suggestion of either accidental or suicidal threat. These are just suspended moments played out on a knife edge stage with an ambiguous, deadpan theatricality. The Neighbours appears to be a perfect illustration of a transitional point between the failed Soviet utopia and Russia’s new Frankenstein capitalism.

Vikenti Nilin

From The Neighbours Series 1993-present

Giclée print

165 x 110 cm

©Vikenti Nilin, 1993

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

Boris Mikhailov’s Case History is a selection of photographs taken between 1997 and 1998 in his hometown of Kharkov, ten years after the dismantlement of the Soviet Union. Mikhailov, a former engineer and self-taught photographer, started the series when he realised the social catastrophe resulting from the transition between autocratic collectivism and capitalist individualism. With their bleeding colours and bad flash exposures, the images document the fall of the Ukrainian men and women who lost everything when the communist safety net was pulled out beneath them. Mikhailov picked his models on the streets of his hometown and, in exchange for food and money, photographed them in various states of undress. Mikhailov justified this by saying that if the subjects appeared clothed they would be invisible and untouchable but undressing them would restore their human identity. Indeed, his photographs contain the kind of images you would normally try to avoid looking at, sights that wear you down to the bone: human wrecks with infected penises, deformed fibrous tissues, badly infected scars healing into absurd shapes, the victims of these misfortunes all smiling through a stupor of drink or drugs while they hurl their bodies through various abuses. The most striking image depicts two shaven-headed, underage kids, one grasping the breast of the other. Later in the series we see the same children sniffing glue from a plastic bag with a bleak, snowy urban landscape in the background.

Boris Boris Mikhailov

Case History

1997-1998

A set of 413 photographs selection illustrated

©Boris Mikhailov, 1998

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

Valery Koshlyakov’s large scale paintings on cardboard, in another room, explore the concept of empire. Covered in paint drips, his flattened box-panels are enlarged postcard images of state approved classical European architecture. The five meter wide piece depicting the Grand Opera in Paris suggests a Stalinist era propaganda mural. The suggestion here seems to be that the grand empires were built on ideological foundations as flimsy as cardboard, falling as dramatically as they were built, leaving behind dripping memories and the forgotten values of a dead regime. With its drips, splatters, echoes of propaganda and choice of cardboard as a media, Koshlyakov comes across as a punk rock, graffiti style Canalleto.

Valery Koshlyakov

Grand Opera, Paris

1995

Tempera on cardboard

345 x 487 cm

©Valery Koshlyakov, 1995

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

Gaeity Is The Most Outstanding Feature Of Russian Art presents us with an opportunity to reflect on a society in which the political system does not consider the individual. Its power lies in its ability to allow us to peer into a culture that, to the western viewer, is almost incomprehensible due to the unique, deeply ingrained social issues that develop in the absence of democracy. While the spectre of the Cold War still looms over many of us, allowing at least a superficial familiarity with Soviet Russia, for those young and fortunate enough to have not experienced this time period, the sense of paranoia, state brutality, famine and cultural oppression must seem shocking, especially in view of the fact that the Soviet regime continued until the advent of Perestroika as recently as 1989.

However, regardless of how graphically the status of post-Soviet Russia is depicted in the exhibition, the Slavic aesthetic remains deeply alien to the western viewer holding the cultural sensibilities of democracy. As Mikhailov himself states, “I think that the phenomenon I am telling the world about is post-communist and post-Soviet in its essence and that it belongs especially to this world, to the Slavic universe.”

[nggallery id=457]

(All rights reserved. Text @ ASX, Laetitia Martinez and David Price, Images courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London)