William Klein is an American photographer. One is tempted to say that he is the American photographer

By Anthony Lane, Excerpt from Nobody’s Perfect: Writings from the New Yorker

William Klein is an American photographer. One is tempted to say that he is the American photographer; among his coevals, only Richard Avedon can match him for stamina and range, and for a visual instinct so sure that you wonder whether both men had cameras implanted in their heads at birth. The difference is that Avedon operates out of New York City, whereas Klein, who will take any chiche you like and bust it wide open, is an American in Paris. One is tempted to say that he is the American in Paris: a more authentic example of the type than even Gene Kelly could pretend to be. Klein speaks English with a French trip of the tongue and French with a hefty American curve to his vowels. He arrived in Paris in the late 1940’s and has stayed ever since, with regular, fruitful forays to other lands. On his second day in the city he met Jeanne, “the most beautiful woman in the world”, who became his wife. They live an a fourth-floor apartment, once owned by Francis Poulenc, that overlooks a northern tip of the Luxembourg Gardens: hard-core Paris, as it were, and quite a switch from 108th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, in Manhattan, where Klein grew up.

He was born in 1928, but the thought that he is now in his seventies is a joke; threescore and ten may be the span of man, but no one has broken the news to Klein, who still behaves as if he was turning one score and five. There is a restlessness, even a sexiness, in Klein’s longevity which can only infuriate those who purport to revel in their youth. He is a big, loping fellow with a mane of white hair swept back over his collar, a roaring laugh that hangs around in his throat, and a pair of Reebok ankle boots on his hind paws. Meeting him face to face, I realized that he belongs to a genus now so rare, so closely identified with another age, that you could be forgiven for thinking it extinct. William Klein is a cat. I am not so experienced a naturalist as to know whether he hails from the species hep, but, like anyone else, I know catness when I see it, and it is there in the Klein limbs, long and loose, in the rotating riffs of his storytelling, and in the peculiar cocktail of ardor and amusement – of engaging hotly with the troubles of the world and then standing back to lend them a cool eye – that instantly summons the scent of the 1950’s.

“I approached New York like a fake anthropologist,” Klein says, “treating New Yorkers like Zulus.”

Klein’s father was in the clothing business; he was all but felled by the Crash, a year after his son was born. There was money and prestige in the family, but it lay with uncles and aunts. (“I can’t say they did anything, ever, for me.”) The young Klein attended the City College of New York, but left before graduating to take advantage of the GI Bill of Rights. He was dispatched by train to Fort Riley, Kansas. “For the first time, I saw America,” he recalls. “I couldn’t go to sleep.” He joined the cavalry – as a radio operator on horseback, which sounds like a surrealist collage – and wound up in occupied Germany. “Someone looked through my record and found that I had got out of university at eighteen, that I spoke a little French, and they chose twenty-five soldiers to go to the Sorbonne,” he says. He never saw action – not the military kind, at any rate. The Klein luck held, and he found himself taking art lessons from Fernand Leger. (“Leger was something else. He looked like Rocky Marciano. He looked like he could take them on. Lee Marvin, the French version.”) Some of Klein’s early paintings – I saw racks of them in one of his Paris studios – show a chunkiness that betrays the muscular presence of his master, although the young man’s talent was always going to be more kinetic than Leger’s, less embarrassed by the force of fleeting. In 1952, some of Klein’s murals were shown in Milan, where he took photographs of them; it was not the first time he had picked up a camera – in a myth that he confirmed to me as accurate, he had won a Rolleiflex in a poker game with other GI’s but it was only then that he understood the firepower of his new weapon.

From here, events moved fast. His abstract shots were featured on the cover of an architectural magazine called Domus and seen by a guy from a fashion magazine called Vogue. This was Alexander Liberman, no less, the art director who could spot talent an ocean away and bring it home. By 1954, the prodigal son was back in New York, on a five-month stay, with a dream brief: come and work for us, carte blanche, two hundred bucks a week, limitless photographic supplies, and while you’re at it, shoot the city. “I approached New York like a fake anthropologist,” Klein says, “treating New Yorkers like Zulus.” He and Jeanne lived in a small hotel; “I would print like a maniac – fifty photos a night, washing them in a bathtub.”

“The whole book ends with a bang: a sun raging low on the Manhattan skyline, printed with such rich pointillist grain that what was, presumably, a nice warm day is cranked up into an artist’s impression of a nuclear firestorm. Just what America wanted in 1956.”

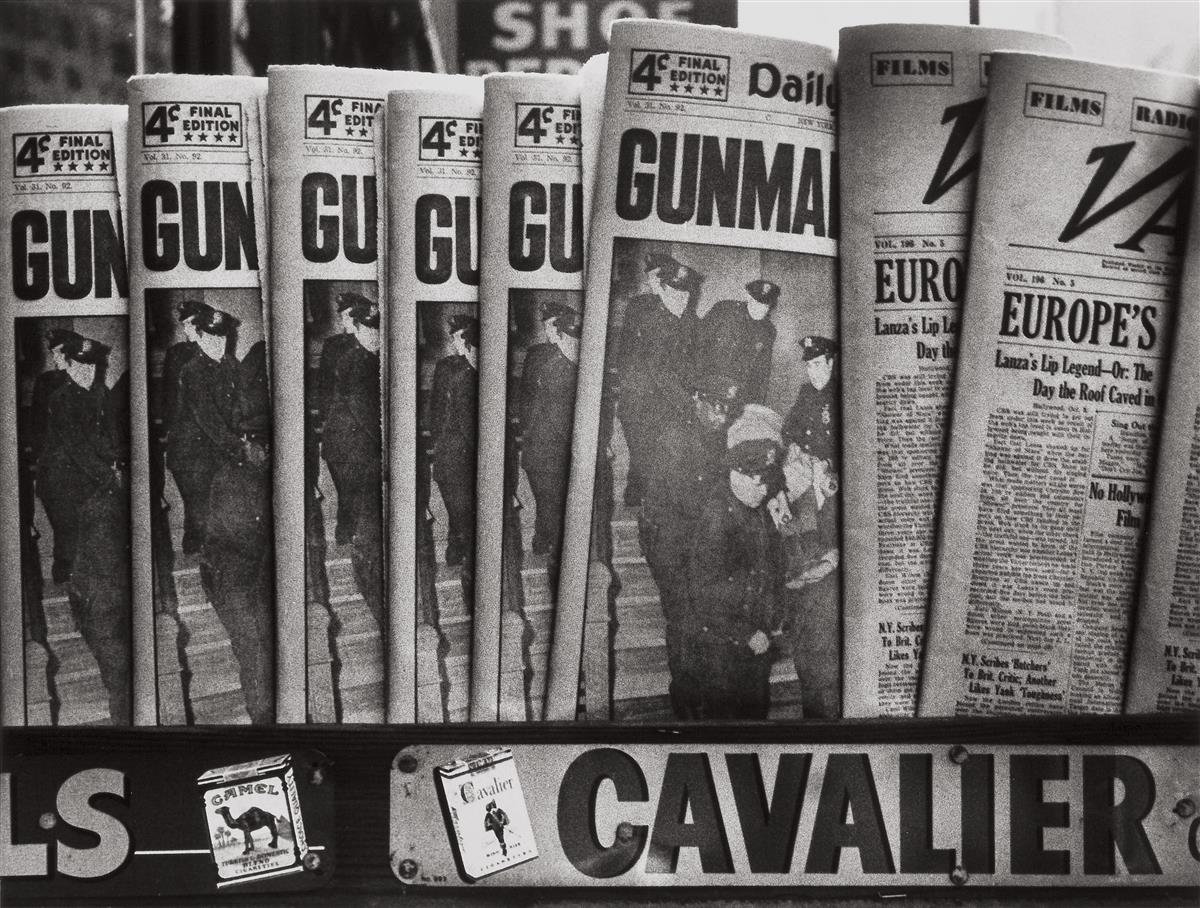

The result was Life is Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, which was published in 1956 – published in France, that is, to instant acclaim. It did not appear in America, a laughable omission that remained uncorrected until the book was reprinted in 1995. New York publishers turned up their noses. “They would say, ‘What kind of New York is this? It looks like a slum.’ I said, ‘Listen. New York is a slum. You live on Fifth Avenue, you come to your office on Madison Avenue – what do you know? You ever been to the Bronx?'” Not only did Klein design the book himself; he alerted readers – those who could get hold of the thing – to the possibility that a photography book, no less than a photograph itself, could be a work of art. “My first idea was to do a collection of the front pages of the New York Daily News.” What emerged was hardly less alarming. There are no captions, and the rhythm of the layout keeps to no known beat: some shots are bordered in white, others leak across the central gutter or spill to the edge. At one point Klein uses a spread to mount an all-out assault; each facing page shows the front of a movie theatre, ablaze with names of the period (Van Heflin, Cesar Romero, Leo Genn) and tilted so that the lights on the marquees bounce and gleam off the enamelled darkness of a car. The whole book ends with a bang: a sun raging low on the Manhattan skyline, printed with such rich pointillist grain that what was, presumably, a nice warm day is cranked up into an artist’s impression of a nuclear firestorm. Just what America wanted in 1956.

Order Nobody’s Perfect: Writings from the New Yorker

ASX CHANNEL: WILLIAM KLEIN

(All rights reserved. Text copyright Anthony Lane, Images copyright William Klein)