By F. Jack Hurley

Originally published in IMAGE: Journal of Photography and Motion Pictures of the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, September, 1973

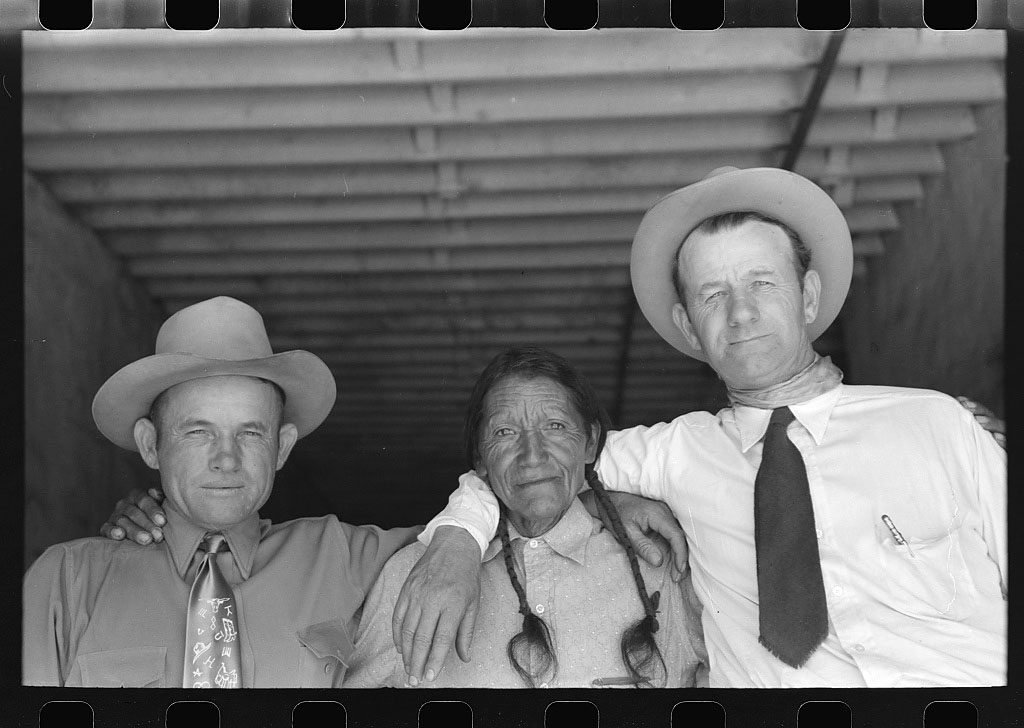

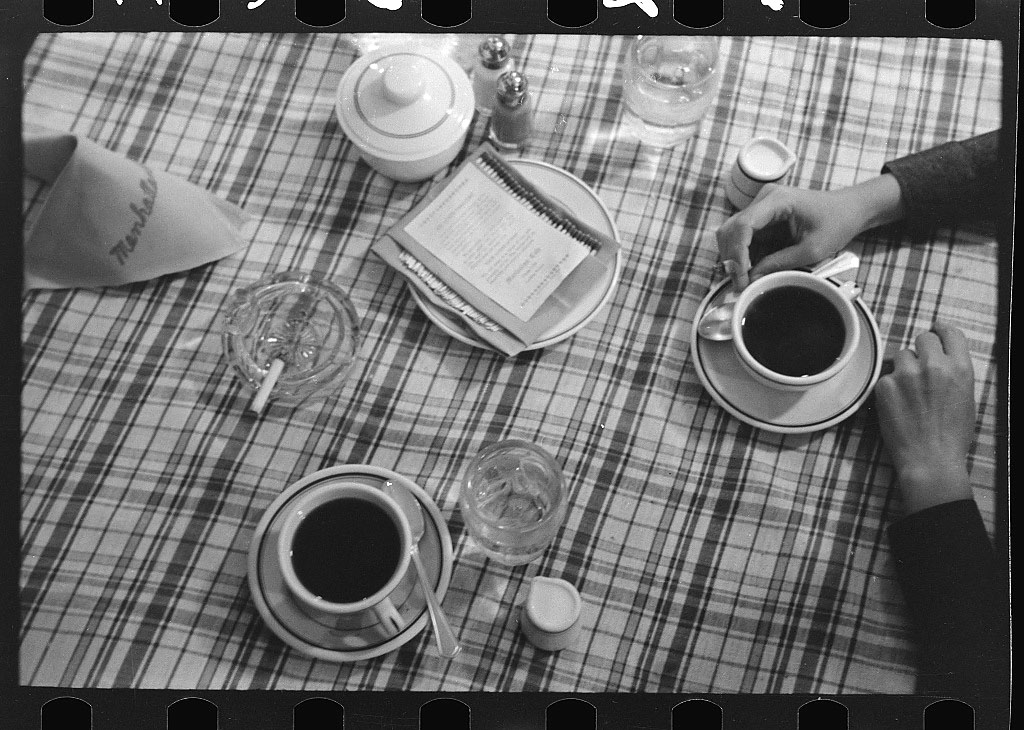

To try to capsulize the work of Russell Lee into a short article is an essentially impossible task. The man has been active in the field of photography so long and in so many different ways. There are certain themes, however, which do assert themselves. Russell Lee is a man who loves people. He is a man of gentle humor and broad toleration. Over the years his subject matter has ranged from social problems to industrial organization but through it all his best work has always exhibited a deep concern for his fellow human being.

In the early days, nobody intended for Russell Lee to become a photographer. Born in 1903 to a comfortable mid-western family, young Rus grew up in sleepy Ottawa, Illinois, was sent at the proper time to Culver Military Academy and finished off his formal education with a Chemical Engineering degree from Lehigh University. He came back to his home town and became plant chemist for a company called Certainteed Products, making composition roofing. A prosaic story if ever there was one.

In 1927 Russell married a talented young painter named Doris Emrick and the two went to Europe on their honeymoon. The next year found them back in the Mid-West where Russell was managing a plant in Kansas City and Doris was studying painting at the Kansas City Art Institute. It was not a bad life, but Russell was bored. Doris’ interest in art was opening new ideas to him and the world of Certainteed Products seemed more and more constricting.

Fortunately, Russell did not have to remain bound to his job by economic necessity. He had a permanent income from some farms which he had inherited. In 1929, as the stock market was crashing and the economy was crumbling into ruins, Russell decided that he wanted to learn how to paint. That year he and Doris began to travel, to San Francisco, to Europe and back to San Francisco. They met Diego Rivera and others who were in the forefront of the artistic movements of the day. From Arnold Blanch they heard about the exciting artists’ colony which was growing up in those days at Woodstock, New York. By the end of 1931 they were at Woodstock where Doris’ talents were flourishing. But Russell was becoming frustrated:

“I think I was looking for something. Yes, I think I was. Well, I tried to be a painter and I realized that I couldn’t be a very good painter because I couldn’t draw very well.”1

For four years, Russell stuck it out. Summers were spent in Woodstock and winters at the Art Students’ League in New York City. For all his frustrations, Lee was gaining a strong background in visual imagery. Whether he ever became a painter or not, he would know what a good picture was. This is a point worth emphasizing, for Lee’s work is often seen as naive. Naive it may be, but the naivete is informed artistically and consciously chosen.

The pivotal event came in 1935 when Lee became the possessor of a small Contax 35mm. camera. A friend named Emil Ganso had suggested that it might help with his drawing. Another friend, Konrad Cramer, had gotten a Leica and the two began to compare notes. It was fun and Lee found himself more and more caught up in the fascination of the fine little machine and the darkroom and the print:

“I got my first camera because, as I say, I wasn’t a very good draftsman and I thought that would help. But I ended up getting interested in photography.”

As his interest in photography bloomed, Russell came alive. Every phase of the process fascinated him. The artist in him found expression in the quick-caught images. The engineer-chemist loved the technical aspects of the work. Soon Lee was mixing his own chemicals from published formulae and “pushing” the films of the day from their normal ratings of ASA 32 (modern rating system) all the way up to ASA 100! He discovered the possibilities (and the limitations) in open flash and began to experiment with early flash synchronizers. It was a happy, productive period. As Lee began to see the world in new terms through the viewfinder of his Contax, he also began to develop a social conscience:

“I got interested in what was going on around the Woodstock community. I went to auctions where poor people were selling off all their household goods. I went to a local election and photographed it at night using the Contax and open flash. . . . I tried my hand at a county fair. That spring I went down to Pennsylvania with some friends and photographed the bootleg coal mines. I was developing a social conscience at that time because people were so damned poor.”

In the winter of 1935, Russell walked the streets of New York, looking for ways to visually express the poverty and misery around him. His sense of humor remained however and when the evangelist Father Divine came up the Hudson River with a whole flock of his angels in train, Lee photographed the event with vigor. By this time, Lee had an agent in New York and was beginning to sell some pictures to magazines. More importantly, he was beginning to evolve distictive elements in his own style and approach to photography.

In later years, Lee’s work has often been thought of in terms of series. The Pie Town series or the San Augustine series spring immediately to mind. Lee became known for his ability to dissect a situation with his cameras and show all of its facets. This ability seems to have appeared quite early. In a recent interview, I asked the question, “Were you looking for one great picture in those early situations or were you thinking in terms of series?” Lee’s answer was illuminating:

“Well, in the case of the auctions I would shoot several pictures —different facets of the auction. It might be the auctioneer or it might be the faces of people selling things, or the audience, or even a pile of belongings. It was not exactly a picture story— not yet—but I was after the many sides of the auction.”

Perhaps it was the background training in the sciences, or perhaps it was merely a natural tendency. Whatever the reason, Lee took pictures in series from the very beginning. Long before most American photographers were thinking in terms of the photo-essay Lee’s mind was moving in that direction. Years later, his friend and mentor, Roy Stryker, summed up the Lee approach to photography in this way: “Russell was the taxonomist with a camera. . . . He takes apart and gives you all the details of the plant. He lays it on the table and says, There you are, Sir, in all its parts. . . .’ “2

Russell was finding his life’s direction by the summer of 1936. He was also getting to know his way around the world of photography. He met Willard Morgan, he attended meetings of “The Circle of Confusion,” a group of people in New York who knew and loved good photography, he became friends with Harold Harvey, the brilliant photographic chemist who developed the 777 formula. Things were falling into place, but the great work was still ahead.

It was in the early summer of 1936 that Lee heard about the work that was going on down in Washington by an obscure farm agency then known as the Resettlement Administration.3 Joe Jones, a painter, told him about the project and indicated that Ben Shahn might be a good man to get in touch with for more information. Lee had met Shahn several times during the years in New York and he knew and respected the painter’s work. If Shahn was involved with the project it must be worth looking into, so Lee bundled a portfolio of prints into his car and headed down to Washington to see if he could fitin. Shahn, of course, was only peripherally involved with the photographic project and could offer nothing but encouragement. He did, however, send Russell over to see the director of the project, Roy Stryker.

I showed Roy a bunch of pictures . . . and he liked them but had no openings. He said, “Why don’t you go over to the Department of Agriculture?” Well, I did that and all they had was a job coloring photographs for the Forest Service. I just turned on my heel and went out of that!

Well, three or four weeks later I got a call from Roy to go down and photograph the Jersey Homesteads housing project. Ben Shahn was living down there and they had a garment workers’ cooperative project going. So I went down there and photographed that. I made a lot of 8×10 prints of different facets of community life. Roy liked them and Carl Mydans was leaving so I got the job.

Lee clearly wanted to work on the Resettlement Administration project because it interested him, not because he needed the job. The USDA job did not interest him and so he “turned on his heel.” The gift of being responsible only to oneself is not given to everyone in the arts, but Lee has used that gift carefully. His financial independence meant that he could wait until the right opportunity arrived without the specter of starvation close by.

By the fall of 1936, Lee was on the RA payroll, working with Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein and Walker Evans on what was to become the legendary FSA photographic project. (The agency’s name was changed from Resettlement Administration to Farm Security Administration in 1937.) Roy Stryker provided direction and bureaucratic protection to the group, leaving the photographers free to compile the greatest documentary collection which has ever been assembled in this country.

Lee’s first trip for the Resettlement Administration was supposed to last six weeks. It lasted nine months. The trip yielded dozens of significant individual photographs and at least one fully developed photo-essay. Lee was sent to the area he knew best, the Mid-West, and soon his pictures were arriving in Washington in regular batches, always accompanied by complete captions and relevant information. (Two of his best early photographs are featured in The Bitter Years, Edward Steichen, editor. They are titled “Old Age” and “A Christmas Dinner.”)4 In early 1937, Russell was still in the Mid-West when the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers flooded. He covered the effects of flooding on rural and small town folk, traveling for weeks in the chaos and muck of a major disaster.

When the floods were over, Russell returned to Indiana where a thought struck him: “The hired man is an essential part of the farm economy. Why not document him?” Roy liked the idea and Russell began to use his camera in the way he knew best, digging into the details of a social situation. The result was an extended photo-essay “The Hired Man.” Although it was never published, “The Hired Man” represented a very definite high point in Lee’s career up to that point. Here he brought to bear all his scientific background and all his skill with a camera to produce a fully realized visual document of social patterns:

“I was interested in how people lived. . . . I felt that the inside of a house was a very important part of showing how people lived. Of course, the outside was important too. You could tell about people by how the flowers were placed and how things were kept up. I became concerned with details. . . . I’d go in a bedroom and maybe I’d see something on a bedside table that would interest me. The things people kept around them could tell you an awful lot about the antecedents of these people.”

Lee’s work was always probing, but also gentle and respectful. He liked the people he was documenting and his work showed it. During his first, long trip for the Resettlement Administration, it was decided that the director, Roy Stryker, should come out and meet him in the field so that they could look at pictures together and talk over general aims. Stryker traveled with him for several days and vividly recalled his ability to gain access into homes where most photographers would never have been trusted:

“I didn’t get out into the field much, but one of my first trips was out to Minnesota or Wisconsin with Russell Lee. We were in a small town and he saw this little old lady with a little knot of hair on her head. He wanted to take her picture but the woman said, “What do you want to take my picture for?” Russell’s response was part of my education as to how a photographer thinks. He turned to the lady and said, “Lady, you’re having a hard time and a lot of people don’t think that you’re having such a hard time. We want to show them that you’re a human being, a nice human being, but you’re having troubles.”

“Well,” she said, “Allright, you can take my picture, but I’ve got some friends, and I wish you’d take their pictures too. Could you come and have some lunch with me today?” We stayed all that day and that night and had supper. She invited four or five women over and Russell took pictures.5

Everyone who has worked with Lee has been impressed with the quality which Stryker describes, the quality of trust. Somehow, he has always managed to take photographs of the intimate areas of people’s lives when most photographers would not have gotten in the door.

People who have seen Lee’s pictures from this period often remark on the stark, almost glaring light which he used. It is true that he was fascinated with on-the-camera flash, which often led to harsh shadows. On the other hand it also yielded details and details were what Lee wanted. I asked him about his use of flash on the camera and his answer was direct and to the point:

“I have always believed in keeping my technique as simple as possible in the field. If I had begun to string wires for multiple flash exposures, I would have lost many important pictures. Remember also I was traveling alone in those days so I had to keep it simple.”

For the next several years, Lee’s life was a busy composite of long road trips and periods of intense activity in Washington, testing new equipment, helping to plan exhibitions and working with the other photographers. Lee’s first marriage had dissolved at about the time that he joined the agency. In 1938 he met a young woman in New Orleans named Jean Smith. The two began working together and before long, Jean was Jean Lee. It was, and is, a good marriage. The two personalities complemented each other and the work went on.

By 1941 the reality of approaching war was looming larger and larger, affecting the United States government and all of its agencies. Lee and the other FSA photographers began to do more assignments emphasizing preparedness and fewer of the rural and small town pictures which they had so enjoyed. Often they were “loaned” to other government agencies to give them the benefit of their expertise. Lee covered several industrial stories for the Office of Emergency Management and was, in fact, photographing the construction of Shasta Dam for that agency when the bombs began to fall an Pearl Harbor.

Since he was already in the West, it fell to Russell to help cover one of the strangest and saddest stories of the war, the removal of the Japanese-American people from the West Coast. With his wife, Jean, he gained access to the homes of the people and followed them through the doleful process of selling their belongings and moving inland to the camps.

It was a tough assignment because you saw these people just herded with tags on them. And you saw their little houses and businesses with the ‘For Sale’ sign up.

The inland camps were decent enough, but desolate, and the job of covering them was not one which either Russell or Jean could have enjoyed. The photographic documentation of this chapter of American history was important work, however, which needed doing. Several of Russell’s best pictures of the relocation are featured in the book Executive Order 9066 by Maisie and Richard Conrat.6 The serious student of American photography (or American history for that matter) owes himself a careful viewing of those photographs.

In December of 1942, Russell and Jean were back in Washington. Jean was working in the Office of War Information and Russell was doing photographic assignments, also for the OWI. One evening an old friend, Pare Lorentz, dropped by for a chat. Pare had directed important documentary films during the depression, including THE RIVER and THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS. Lorentz had been asked by the Army Air Force to put together a unit of top professional photographers to photograph the routes and airfields of the Air Transport Command. Since American pilots often found themselves flying into airfields which were completely unfamiliar to them, often on radio silence and with only the crudest navigational devices, some good means of visual briefing before flight was needed. Thus there was an immediate need for good clear still photographs and movies. The army was willing to give the project high priority and they wanted the best. Would Russell take on the job of shooting stills?

Lee was 39 years old in 1942, hardly a callow youth. He did not have to go to war. Jean was not entirely enthusiastic about the separation either. In a recent interview, the two reminisced about the decision to go with the Air Transport Command:

“Russell: So, Pare was putting together this organization and he wanted me to be in charge of the stills. Now, Pare was a great salesman and he decided that if he could persuade Jean that everything would be all right.

Jean: (Laughing) He told me firmly that if Rus would go into it I could meet him at least once a month at the Shephard’s Hotel in Cairo, Egypt, and have a wonderful holiday. He said Cairo was one of the most fascinating cities in the world and everything would be fine. Now, of course, I never believed a word of it, but this was the sort of thing he was feeding us.”

Eventually, Pare’s salesmanship (coupled with Russell’s desire to be a part of the national effort) won out. Russell received his commission as a Captain on January 31, 1943.

The army high command was as good as its word. The photographic project was given number one (Presidential) priority. A B-24 bomber was assigned to them and specially modified for aerial photography. The nose was converted to high-grade glass and the waist and tailgunner’s positions were also modified to accommodate the needs of photographers.

The first real mission of the photographic crew in their glass-nosed bomber covered an incredible amount of territory. For four months the crew flew almost non-stop along the southern transport route from Florida to Puerto Rico and Trinidad, on to Brazil, across the South Atlantic to Ascension Island, on to Accra and Dakar, over the Sahara and Atlas Mountains to Marrakesh. From Marrakesh in Morroco, all U.S. transport plans branched off in two directions, one to the North into Britain and the other to the East. The photographic crew dutifully followed out both routes. Eventually Russell reached Cairo (Jean was not there). From Cairo the group headed East via Khartoum, Aden and Karachi and finally turned for home. When the first mission was over Russell had lost 22 pounds, had the beginnings of a first-class ulcer, and was ready for a rest.

For Russell and Jean the war settled into a weary routine of long missions overseas (Jean remaining in Washington to work for the OWI) and short rest periods. The photographic unit was tight-knit and professional when it was on the job, but Jean recalled that they were anything but military when they were in Washington:

“At one time, somehow, Pare decided that they weren’t really acting in a military fashion and that they ought to start drilling every day. Well, the office was right across from the Washington Monument grounds, so Pare gave an order that the ten or twelve of them would get out every morning and drill on the grounds. For about three mornings they drilled and somebody called up and said, “Get those guys off the grounds! They don’t know how to drill. They don’t know how to do anything!” And this was the end of the military drilling.”

In 1944 the photographic group went to the Far East. Operating out of New Delhi, the group covered air bases in Ceylon and India and eventually flew “The Hump” into China. As the still photographer for the group, Lee’s duties included quite a lot of work on the ground in addition to the aerial photography. He was expected to photograph the base facilities and military living conditions so that the high command back in Washington would have a visual check on how the remote bases were being run. At his own suggestion, he began to get out into the countryside wherever possible and photograph the impact of the war on the local people. Some of his finest photographs from this period were done during these occasional sorties into the countryside. Here the humanist in Lee could reassert itself and he could concentrate on people again.

Looking back on his years in the Air Transport Command, Lee could see some benefits to himself as a photographer. He did become quite expert in aerial photography, a skill he would put to use on many later industrial assignments. He did develop a very quick “eye” for photographs, for one cannot always turn a B-24 around to pick up a lost shot. And finally, he became more familiar than ever with the 4×5 format. “You got to the point where you automatically placed a 4×5 frame around whatever you saw,” he recalls. On the whole, however, the war was an exhausting and often frustrating experience for Russell and he was ready to get out of the service as soon as possible.

When the war was over, Russell was in Portland, Oregon, having just returned from a mission in Alaska. He headed immediately for Washington, D.C., and Jean. When he arrived he learned that a new special order had come through allowing anyone over forty to get out of the Army immediately. Russell, aged forty-two, got out. Within ten days of the end of the war, the Lees were out of Washington, heading west.

After a stop in Dallas, Texas, to see Jean’s parents, Russell and Jean retreated to the country. Both were mentally and physically exhausted and Jean swore that she would never go near a city again. For weeks they stayed in a cabin on Lake Buchanan near Austin, Texas. (Russell’s love affair with the Texas Hill Country goes back to early trips for the FSA and continues to the present.) When the weather became too hot they headed for Colorado. There, in the remote wilderness of the western slope, reality and responsibility caught up with them.

Russell and Jean had been staying at a ranch near the tiny village of Lake City, Colorado, for about three weeks when a ranch hand came running up to them, out of breath and wide-eyed. “The White House is calling!” he gasped. Sure enough, Pare Lorentz had a new job for Russell and he had gotten the White House operator to locate him. Five days later, tired and dishevelled, the Lees arrived in Washington. The next morning, Russell reported for work.

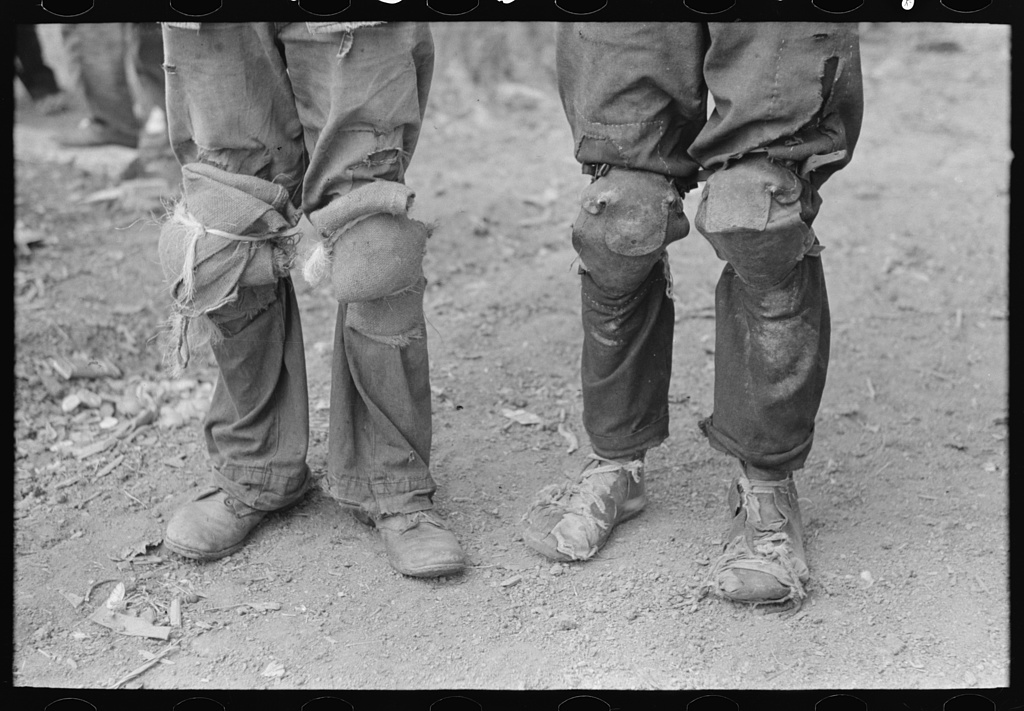

The situation which had brought the Lees out of their short-lived retirement was an emergency in the nation’s bituminous coal industry. In the spring of 1946 the country had suffered widespread and bitter strikes among the coal miners. The coal mining industry had been under tremendous pressure to produce during the war and there had not always been time to put the welfare of the worker first. As long as the nation had been at war, the miners had accepted their lot as a patriotic duty, but now the war was over and they were determined to improve themselves. In some cases their haste led to violence and destruction. The Truman Administration, anxious to determine just what sort of conditions did exist in the bituminous coal industry, commissioned a group of Naval officers who were experts in the field of health to work through the Department of the Interior on a survey of health, housing and mining conditions. The people who planned the survey realized at the outset that a report of the type they envisioned would need illustrations and Lee seemed the best man for such a job.

After a series of high speed orientation trips through the coalmining areas, Russell and Jean were sent out more or less on their own to seek the photographs which would illustrate the weaknesses and the strengths of the coal mining industry. It was a good feeling to be back on the road again, doing the job that they both knew how to do best. The work was essentially an extension of the work Russell had done for the FSA and he knew just how to approach it. For the next seven months the Lees were on the road most of the time. They talked to hundreds of miners and their families, sat at their tables and learned their way of life. The work yielded over 3000 negatives and many of the images were to be among Russell’s best.

The information specialist on the health survey of the coal industry was an old friend of the Lees, Allan Sherman. It was his job to travel with the survey team and make certain that the local communities understood who they were and what they were doing. He also did much of the writing of the final report. In a recent visit to Washington I found Sherman still working for the Department of the Interior. He seemed pleased to take a half an hour to talk about the miners’ crisis and Russell Lee’s work. “Russell Lee,” he said, “has a great talent for establishing rapport very quickly with people. People simply trust him and before you know it he is taking pictures which no one else could possibly have gotten.”7

The completed report, titled A Medical Survey of the Bituminous Coal Industry was published in 1947.8 It contained hundreds of Lee’s photographs as well as a very detailed discussion of health conditions in the mines. The last sixty-seven pages of the book contained a supplementary section designed to humanize the problems which had been discussed in more or less abstract terms on the pages before. The supplement was called “The Coal Miner and His Family.” It was written by Allan Sherman and, of course, illustrated by Russell Lee. Because it expressed the problems of the mining camps so powerfully, the Department of the Interior re-issued “The Coal Miner and His Family” as a separate publication. Its quality holds up quite well today.

The work that Russell Lee did for the Department of the Interior in 1946 and 1947 is important for two reasons. Visually it was very strong. It represented some of Lee’s best social photography. But on a political level it also had en impact. Allan Sherman said of the report, “It had a great deal of influence in eliminating company housing, company stores and improving health facilities.” Today the photographs which Lee made for the medical survey of the coal industry are still kept together, along with their negatives and contact prints, at the Department of the Interior. The collection remains under the careful custodianship of Allan Sherman.

When the work for the Bureau of Mines was over Russell and Jean returned to central Texas, the area they were beginning to think of as “home.” The spring of 1947 found them back at the cabin near Lake Buchanan and by that summer they had found a permanent home in Austin. Russell began to take on occasional commercial jobs and Jean, good Texas Populist that she is, became deeply involved in the liberal wing of the local Democratic Party.

During the late 1940’s, Lee began to take occasional commercial assignments. His old friend and boss, Roy Stryker, had gone to work for the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) and was directing the photography for Standard Oil’s house organ, The Lamp. Stryker had attracted a staff of fine photographers which included at one time or another “Esther Bubley, John Vachon, Harold Corsini, Gordon Parks, Eliot Erwitt, and many other top names in the field. The Lamp stood in a class by itself among the private magazines of its day and has provided the prototype for the best house organs since. Lee had no desire to be a staff member of any magazine, but he did take assignments for The Lamp—when those assignments interested him. Over the years Russell worked on stories ranging from modern cattle ranching in west Texas (using helicopters and trucks to work the cattle) to prospecting for oil in swamps of Louisiana.

As is often the case, Lee’s work for The Lamp led to other commercial assignments. He did considerable work for Fortune magazine in the late 1940’s and that relationship continued well into the 1960’s. He also took several major assignments for Dow Chemical Company. In the mid-1950’s he visited the Middle East twice for Arabian American Oil Company. Lee was a good industrial photographer. His background in chemical engineering stood him in good stead in this area. He understood the processes involved and could appreciate the pleasure felt by an engineer in contemplating a well-run plant. As always, however, it was the human aspects of industrial processes which interested him most and which elicited his best work. For example, while he was on the Middle East assignments for Aramco he became fascinated with the company’s relationship with the local people. As a part of their contractual obligation, the company was training native Arabs to assume responsibility for the local operation. Many skills necessary to the running of a refinery or the locating of or drilling for oil were simply foreign to the regional population. Lee recalls photographing Saudi Arabians being taught to use a hammer and nails. Coming from a treeless culture, they knew nothing of such basic industrial skills.

Lee enjoyed his commercial photography but it never dominated his life. For one thing, Jean never fully approved of his working for such industries as Standard Oil and Dow Chemical. She never quite understood the aesthetic pleasure that could be gained from probing into the visual intricacies of a complex industrial process and her background and training had imbued her with a deep-set distrust of all big business. In addition, Russell himself never felt the necessity to take every assignment that was offered him. In a recent interview, I asked him about his industrial work. His answer was worth repeating.

“Hurley. Isn’t the basic problem in commercial photography to please someone else?

Lee: Yes, in a way I suppose it is, but I also had to please myself. There is a real distinction between straight commercial photography and professional photography, you know, and I think it is important to make that distinction. A commercial photographer is a camera for hire. If a job didn’t really engage my interest, I didn’t take the job. My first responsibility was always to myself.”

In the years since World War II Lee has been quite successful as a professional photographer, often receiving assignments which paid very well. There were also many jobs, however, which he did on his own simply because he wanted to do them. Often these involved little or no money and, as might be expected, they included some of his best work from that period. In 1950 Lee worked with the University of Texas on a major study of Spanish-speaking people in Texas. The study included living conditions and health problems among Latin-Americans. In those early post-war days, the Spanish-speaking people were often the poorest and most exploited folk in the Southwest. Their problems needed airing and Lee was glad to be involved. In Corpus Christi, Texas, he found a local doctor, Dr. Hector Garcia who let Russell accompany him on his daily rounds through the Spanish-speaking ghetto. It was an eye-opening experience, for living conditions were often as bad as or worse than any he had encountered before—and this was supposed to be affluent Texas! The study included San Antonio, San Angelo and El Paso as well as Corpus Christi and when it was done, the University of Texas was in possession of a thorough visual analysis of the problems of Latin Americans in the Southwest.

Over the years Russell shot many stories for the Texas Observer, a small but extremely influential newspaper published in Austin. In a state which has traditionally been deeply and unthinkingly conservative, the Texas Observer has often been forced to play the role of a still, small voice of reason. It has never been a wealthy newspaper (it has lost money in far more years than it has made money) but it has spawned some of the finest journalists and writers that have been seen in this country in recent years. People like Ronnie Dugger and Willie Morrris cut their journalistic teeth by nettling the Texas power structure from the pages of the Texas Observer. One of Lee’s finest stories for the Texas Observer involved a series of visits to state institutions for the elderly and the insane. The images that he recorded in those places were stark and terrifying. Then as now, the elderly and insane were society’s forgotten people and Lee’s pictures made this bitterly clear.

Jean’s interest and involvement in the close-knit world of liberal Texas politics led Russell into photographic coverage of many political events and leaders. The Lees developed a long-standing friendship with Senator Ralph Yarborough and Russell took hundreds of photographs of his variegated career. Russell was at his best capturing the still rural face of Texas politics during the 1950’s. In those days the political processes to a large degree hinged on watermelon and barbecue and hot summer afternoons under the live-oak trees. Lee’s cameras caught it all far better than it can be described in words.

In 1960 some friends on the staff of the University of Texas suggested that Russell should work with Professor William Arrowsmith on a special issue of the prestigious Texas Quarterly. Arrowsmith, a specialist in classical languages, was editing a large number of articles by Italian scholars for publication in one addition. The title of the special Texas Quarterly was to be The Image of Ita/y.9 What would be more natural than to commission a fine photographer to secure some sensitive images as illustrations? Arrowsmith got a small grant to help finance Russell’s trip and the two of them went to Italy.

Well, from a commercial standpoint, the trip was nothing. There’s no question I lost money on it! But so what. I like the pictures that I got over there and I think that’s what really counts when it’s all over.

Looking back, Lee insists that he approached Italy as a tourist; but if that was the case it was as a tourist with years of experience in visual imagery. His sense of light, his ability to capture fleeting expressions, his love for the poetry of the human body all reached heights of expression which he had seldom achieved before. At the age of 57 Russell Lee was still growing photographically, still learning, and still maturing.

Between the creative high points, Russell and Jean took life pretty much as it came to them in the post-war years. When an assignment came along that interested Russell he took it. If it paid, fine, if not, it wasn’t terribly important. If there were no photographic jobs on the horizon, there was always the fishing at Lake Buchanan or up in Colorado. Russell and Jean had known years of intense pressures during the depression and the war and they were ready to avoid really high-level pressures for a while. It required a matter of considerable importance to bring the Lees out of Austin.

One event which was always certain to claim their attention was the annual photo-workshop which was held at the University of Missouri for two weeks each fall. The University of Missouri’s Photo-Workshop was the brain child of Clif Edom who taught photography in the Journalism department there. His idea was to bring in a hand-picked group of advanced young photographers and place them under the influence of the masters in the field. Roy Stryker took part in several of the early workshops. Other top names were there too. The workshops began in 1948 and have continued to the present as one of the finest learning experiences in the world of photography. Russell attended the second workshop as an instructor in 1949 and served on the staff for the next thirteen years. For eight years he and Jean were designated co-directors.

The worksnops were carefully structured by Edom to give the most intensive sort of training to the young photographers who were selected to take part. Each year a small town in Missouri was chosen for a thorough photographic analysis. The group would attempt to identify and visually portray the town’s power structure, its economic base, its problems and its strengths. The formula seems to have worked, for the staffs of many of the finest magazines and newspapers in the country are seeded with “graduates” of the University of Missouri’s Photo-Workshops.

During those short, intense weeks in small Missouri towns it became clear that Russell was a really fine natural teacher. He was patient and open minded and he had the magic knack for positive criticism which sent the student out anxious to do more. Luckily for a generation of students, the University of Texas recognized his skill and brought him on to its faculty on a permanent basis.

In 1964 friends in the Art Department at Austin asked Lee if he would be interested in doing a major retrospective exhibition. Lee thought it over, discussed it with Jean, and they decided that it might be a good experience. The next year Russell gave a show. In beautiful enlargements ranging up to 30×40 he presented over 400 prints spanning his whole career. The exhibition covered an entire floor of the University’s spacious art center and was very well received. As a direct result of the exhibition, Lee was asked to design and teach the first photography course ever offered by the University of Texas’ Art Department.

Since 1965 Russell Lee has taught Texas art students about a way of seeing and a philosophy of life. As an almost incidental thing, he has also taught them a great deal about photography. I visited some of his classes this spring and they were a delightful experience. The air was full of freedom and his students obviously loved him very much. One morning we all trouped out to a sunny hillside for a group portrait and the enthusiasm and high-spirited exchanges between Russell and the young people turned what could have been a mundane moment into a festive occasion. Several students told me that they had spent a year on a waiting list to get into the basic photography course, “but it sure was worth it.” Later that day Russell and I talked about teaching photography.

Since the course is in the Art Department and is designed primarily for art students who have never held a camera before, Russell’s approach has been quite different from the methods used at the Missouri photo-workshops. There is far less noticeable organization, far less structure. Students are not sent out on explicit assignments. Instead they are introduced to a 4×5 view camera and a series of exercises designed to show them how light works. Later they are told to pick an area one-hundred feet square and photograph its ecology without any supplementary lighting or posing. This is designed to familiarize them with the different possibilities inherent in camera positions from the ultra close-up to the longer shot.

As they reach an advanced level they are encouraged to photograph people with a 35mm. camera. One exercise suggests that they pick one friend and photograph him or her intensively. In this way they are gradually led to a thorough understanding of the capabilities of the camera and encouraged to grow in their own visual capacities. Some go into careers in photography, many remain in other branches of art. It doesn’t matter to Russell. The important thing is to learn to see—honestly.

I’ve always told the students, you must be honest with this camera. If you find that you have taken a picture which is untrue you must never let it be used. You must kill it.

This spring Russell Lee reached the University of Texas’ compulsory retirement age of seventy. The news came as a shock to many of his friends for one simply doesn’t think of Russell retiring. He is one of the youngest seventy year olds I know. I asked him what he had in mind for the future and his answer was typical.

Oh, Jean and I are going to take a good long trip to the West this summer. We’ll probably see how the fishing is up around Lake City, Colorado and we are going to see some friends. Later we will come back to Texas and see if the bass are biting up at Lake Buchanan.

“Do you suppose you will take a camera or two along?”, I asked. “I wouldn’t be surprised if I did.” He smiled. “No, I wouldn’t be surprised if I did.”

F. Jack Hurley

1. All quotes from Russell and Jean Lee were taken from a series of nine tape-recorded interviews which were conducted by the author in Austin, Texas, May 15, 16 and 17, 1973, under the sponsorship of the Memphis State University Office of Oral History Research. The tapes are at present untranscribed but will eventually be available to scholars through the Mississippi Valley Archives of Memphis State University. The author wishes to express his special thanks to Russell and Jean Lee for their help in preparing this article.

2. F. Jack Hurley with photographic editing by Robert J. Doherty, Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties, Baton Rouge, 1972, p. 148.

3. The formation and function of the Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration, are fully discussed in Sidney Baldwin’s Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration, Chapel Hill, 1968. For a discussion of the photographic work of Stryker’s unit see F. Jack Hurley’s Portrait of a Decade.

4. Edward Steichen, ed., The Bitter Years: 1935-41, New York, 1962.

5. Quoted from Roy Stryker in Thomas Garver, ed., Just Before the War: Urban America from 1935 to 1941 as Seen by Photographers of the Farm Security Administration, Balboa, 1968.

6. Maisie and Richard Conrat, Executive Order 9066, California Historical Society, 1972.

7. Allan Sherman, Public Information Officer, Department of Health and Safety, Bureau of Mines, United States Department of the Interior, interviewed by F. Jack Hurley, Arlington, Virginia, June 4, 1973. Tape-recorded, untranscribed, Mississippi Valley Archives of Memphis State University.

8. Rear Admiral Joel T. Boone, M.C., U.S. Navy, Director, A Medical Survey of the Bituminous Coal Industry, Washington, 1947.

9. William Arrowsmith, ed., Photographs by Russell Lee,

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

F. Jack Hurley, who teaches in the Department of History at Memphis State University, grew up in Texas, and was the “school photographer” at Austin College, Sherman, Texas. From 1962 to 1966 he took about 3000 photographs documenting New Orleans jazz for the archives of Tulane University in New Orleans, where he eventually obtained his Ph.D. in American history. His Ph.D. dissertation on photographers of the FSA was published in 1972 as Portrait of a Decade.

George Eastman House

Author : Pratt, George C., ed.

Title : IMAGE: Journal of Photography and Motion Pictures of the INTERNATIONAL MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHY at George Eastman House

Volume : 16

Number : 3

Date : September, 1973